I was still feeling the effects of the lunar eclipse in the early hours of Monday on Tuesday morning. Not in a spiritual way, I was just knackered from staying up. However Croxden, the first stop on my rambles around the North of the shire last week, was a sight for my sore eyes. The tiny village is dominated by the ruins of a Cistercian Abbey founded in 1176 by Bertram de Verdun of Alton Castle (1) for the souls of his predecessors and successors.

Remains of 12thc Alton Castle founded by Bertram de Verdun.

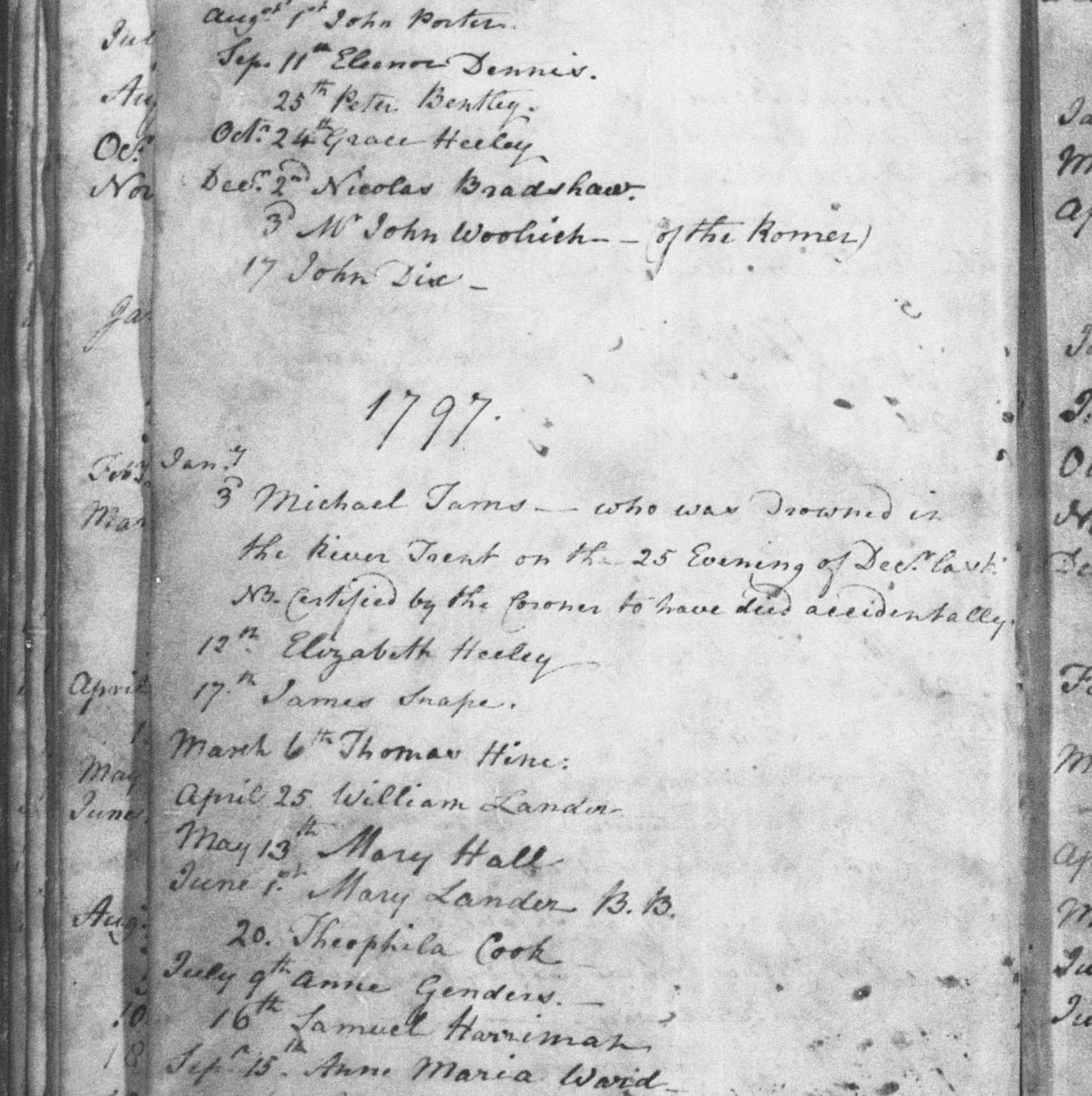

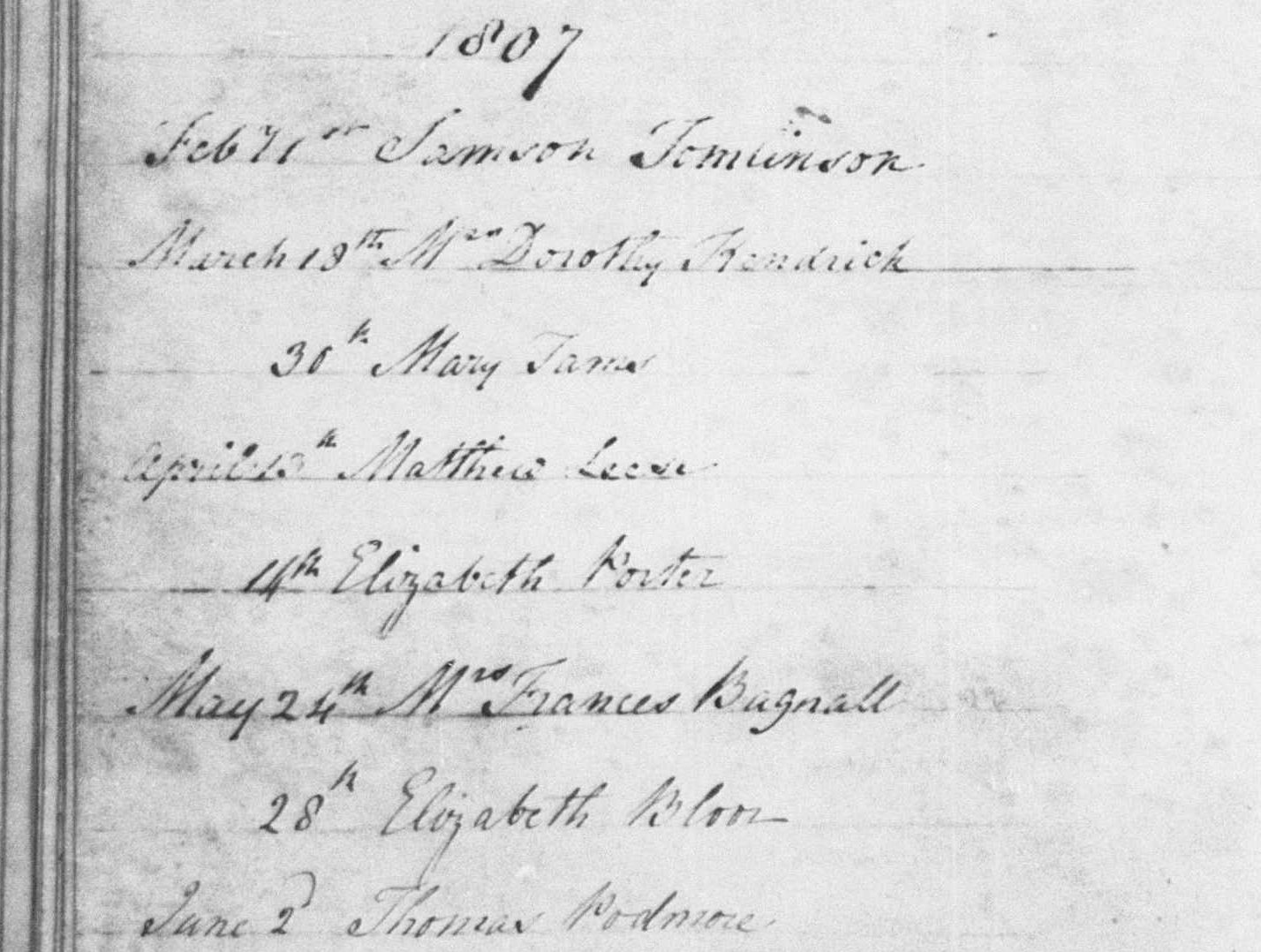

What is left of the semi-circular East end of the abbey church, unusual in England and probably inspired by the French designs the Abbey’s patrons would have known, lies to one side of the road that someone decided to cut through the site. The nave, south transept and other monastic buildings lie on the other and you can see a plan showing what is still visible above ground and what has been lost here. In 1288, a priest from Walsall called William de Schepisheved, was given the task of chronicling life inside and out of these Abbey walls. He worked backwards to 1066 and contemporaneously until 1320 when the entries in his hand stop, although the chronicle continues until 1374.

Blood Moon. Just in case you didn’t see one of the three million photos of it shared online,

We tweeted and shared our photos of the lunar eclipse. William the Chronicler recorded the celestial events he witnessed in the annals. Understandably for him and those of his time, eclipses were considered bad omens, often linked to any conflict, pestilence or bad weather that occurred. William records a solar eclipse in July 1330 and connects it to the floods and unseasonable weather which occurred two months before and for three months after, resulting in a late harvest, “…they had scarcely reaped the last of their corn with the greatest toil on the feast of All Saints and they had at last collected their peas into barns and outhouses on the feast of the blessed apostle Andrew. And what is so remarkable to see and hear, on the feast of All Saints and of St Martin fresh peas in their shells were given to the convent in the refectory instead of pears and apples”. Another notable event in July 1301 appears in the Abbey’s annals describing how, “on the day of the Blessed Mary Magdalene, about the sixth hour, a great earthquake took place, to such an extent that all the persons in the convent, being at their first refection, were dismayed with a sudden and unlooked-for trembling”.

The chronicle also documents a connection between the abbey and Lichfield. William recorded that on Easter Eve in 1313, the great bell of the Monastery was broken by mischance and a man called Henry Michel came from Lichfield with his youths to cast another. It was reported that his first attempt failed but he started afresh and completed by the Festival of All Saints. It seems likely that this was Henry the Bellfounder who granted Lichfield’s Franciscan Friars the springs near Aldershawe which would later supply water to the whole of the city.

Plaque on Lichfield’s Clock Tower, the base of which was once the water conduit which stood near the Friary.

As well as life at the abbey, Death inevitably also features in the chronicle. There are the descriptions of the burials of the Verdun family including that of Lady Joan Furnival, eldest daughter and heir of Theobald de Verdun, who on October 2nd 1334, “was taken by untimely death in childbirth; for on the day she died she was only thirty years and almost two months” and was “buried near her ancestors between Lord Nicholas de Verdun, son of the founder, and her ancestor and Lord John de Verdun, her great-grandfather”. Their now empty stone coffins can be seen alongside the ruins at the east end of the church.

Stone coffins at Croxden.

The entry for 1349 simply and bleakly says, ” There was a great pestilence throughout the whole world.” Nothing more. No indication of how many succumbed to and how many survived the plague here in Croxden. The following year, 1350, another single sentence notes, “This year was a jubilee” (2), and then there is nothing until the harrowing entry made in 1361 which records, ” A second pestilence took place, and all the children that were born since the first pestilence died.” In the absence of detail, I did a little reading between the lines. After ten years, plague had reared its ugly head again and although overall mortality rates were lower than in the first outbreak, the disproportionate number of deaths amongst the young in this second wave led to it being known as ‘the Children’s Plague’. Was this was because those who had survived the plague the first time around had some sort of immunity that the children born subsequently did not? I don’t know. I’m not sure that anyone does for sure. In 1369, another ‘visitation’ is recorded.

Five years later the Chronicle ends but not before recording two further natural disasters affecting the Abbey – a flood destroying all the grass growing near the water together with all the bridges across the River Churnet, and a tempest which took the lead off the dormitory, infirmary, and abbot’s chamber, throwing down half the trees in the orchard. Plague and poor harvests took their toll and by the end of the fourteenth century, the Abbey was in decline.

One thing that doesn’t seem to appear in the Chronicle is the ‘fact’ that King John’s Heart is buried at Croxden. Possibly because it isn’t. I first came across the claim in Arthur Mee’s guide to Staffordshire and since have found several other sources saying the same, including William White’s Directory of Staffordshire (1851), Samuel Lewis’ Topical Directory of England (1831) and The Gentleman’s Magazine (1823). Trouble is other, more reliable sources say it’s at Croxton, Leicestershire including the Charter Roll of 1257. I’m sorry to say, I think we have to concede this one to our foxy neighbours.

A drawing of the effigy of King John in Worcester Cathedral from “HISTORY OF ENGLAND by SAMUEL R. GARDINER

The King’s bowels were also said to have been removed at the time of his death and buried somewhere in Croxton, and to quote Simon Schama, their removal left John, ‘as gutless in death as he was said to have been in life’. The majority of John’s body rests in Worcester Cathedral, although more in pieces than at peace. When the tomb was opened in 1797, it became apparent that the bones had been disturbed, with the jaw lying by an elbow and all but four of the teeth and most of the finger bones missing – the King’s hands presumably having fallen into the hands of souvenir hunters.

The end of the road for Croxden came on 7 September 1538 when Dr. Thomas Leigh and William Cavendish received the surrender of the abbey and the roof was removed to prevent the Abbot and resident six monks from continuing to use the site. Although Croxden Abbey has been privately owned since then, it has been under state guardianship since 1936. Today, the ruins are cared for by English Heritage and it’s absolutely free to go and explore them (although I’m sure they’d appreciate a donation). Unlike staying up all night to watch a lunar eclipse, I can highly recommend it. More information on visiting and directions here.

Notes

(1) I had no idea there was a castle at Alton until I went to Alton with a friend and saw a sign for it. As we found out, it is not open to the public.

(2) I suspected that a jubilee in this context did not mean what I thought it did so I of course googled it and discovered that jubilee years had been started by Pope Boniface in 1300, and to be celebrated every hundred years thereafter. However, Pope Clement VI later amended this as people’s average lifespan was too short and so many would not live to see one. Plus there was money to be made from pilgrims. Pope Paul II later amended the frequency of jubilee years to be every twenty five. For anyone interested, the next one will be in 2025.

Sources:

https://lichfieldlore.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/094-2009web.pdf

Self-representation of Medieval Religious Communities Anne Müller, Karen Stöber

CROXDEN ABBEY: ITS HISTORY AND ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES.

BY CHARLES LYNAM )(North Staffordshire Field Club)

The Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 89, Part 2

![Hanging Bridge, Mayfield by John M [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://lichfieldlore.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/hanging_bridge_mayfield_geograph-3535819-by-john-m.jpg)