When they were excavating the Wyrley to Essington canal at Pipehill at the end of the eighteenth century, a 500 yard section of a Roman military barricade (or palisade) made from trunks of oak trees was discovered.It was thought to have originally stretched from Pipe Hill to the Roman settlement at Letocetum. Well, unfortunately I didn’t come across that (if it even exists anymore) on my walk from Pipe Hill to Wall and back. But here’s what I did find…

A lovely view of the city accompanied me for part of the way (although I can only count four spires. If it’s Five Spires you’re after, look here)

Not too far down the road, I peered over a bridge to see the disused railway line that runs from Lichfield to Walsall. You can get down to the track, although as I was on my own I didn’t risk it, the bank being steep and me being notoriously clumsy. I wonder how far you could walk along the overgrown rails? Rather than regurgitate a history of the railway here, far better is to direct you to the people who really know what they are talking about – the South Staffs Rail group. Their website, full of information, photographs and videos of the line, as it was and is, can be found here, and you can also find out about their campaign to have the line reopened.

Not too far down the road, I peered over a bridge to see the disused railway line that runs from Lichfield to Walsall. You can get down to the track, although as I was on my own I didn’t risk it, the bank being steep and me being notoriously clumsy. I wonder how far you could walk along the overgrown rails? Rather than regurgitate a history of the railway here, far better is to direct you to the people who really know what they are talking about – the South Staffs Rail group. Their website, full of information, photographs and videos of the line, as it was and is, can be found here, and you can also find out about their campaign to have the line reopened.

As I continued along Wall Lane, the wind was blustery and the sky dark and it almost felt autumnal. However, with bluebells and stitchwort along the roadside, hawthorn in the hedgerows and the swallows flitting over the fields of oilseed rape there was no real mistaking this was the merry month of May. I saw pheasants and rabbits and heard and saw all kinds of birds whose names I don’t know, but wished I did. However, all attempts to photograph them ended like this. I’m sticking to bricks and stuff that doesn’t move.

Up at St John’s in Wall, I was pondering what might have once stood here on the site of the modern(ish) church built in 1830. Some have speculated a shrine to Minerva, but my thoughts were interrupted by this graffiti on the church yard wall.

Up at St John’s in Wall, I was pondering what might have once stood here on the site of the modern(ish) church built in 1830. Some have speculated a shrine to Minerva, but my thoughts were interrupted by this graffiti on the church yard wall.

I’ve got a real thing about names carved into stone anyway, but I really have to admire the chutzpah of B Thornton of Redcar in Yorkshire for leaving practically a full postal address. Wish there was a date though… It seems he or she wanted people to know that that they’d been here but just what were you doing in this small, ancient Staffordshire village B Thornton of Redcar? Were you here to see the ruins too?

Whilst I was taking this photograph of buttercups growing where Romans once slept, I remembered that bit of childhood folklore about holding one beneath your chin to see if you liked butter. If you’re interested in science stuff, the explanation for how buttercups make our chins glow is here. It seems appropriate to share its Latin name here – ‘Ranunculus acris’. I think the acris bit means bitter, and I wonder if the flower’s common name started out as bitter cup and got corrupted on account of its beautiful golden colour? Anyway, back to the ruins.

Out of everything, it’s the remains of this small Roman street, with some of its cobbles still intact that gives me the strongest sense of connection with the past. Perhaps it’s the knowledge that you are treading the exact same ground as those who walked here thousands of years ago? Or perhaps I’d spent too much time here, alone with my thoughts….

Out of everything, it’s the remains of this small Roman street, with some of its cobbles still intact that gives me the strongest sense of connection with the past. Perhaps it’s the knowledge that you are treading the exact same ground as those who walked here thousands of years ago? Or perhaps I’d spent too much time here, alone with my thoughts….

Heading out of Wall, there’s a farmyard wall which I believe was built using stone robbed out from the Roman site. Oh and another little mystery – just how does a pair of pants end up in a hedgerow like this? On second thoughts, this is one I probably don’t want to know the answer to.

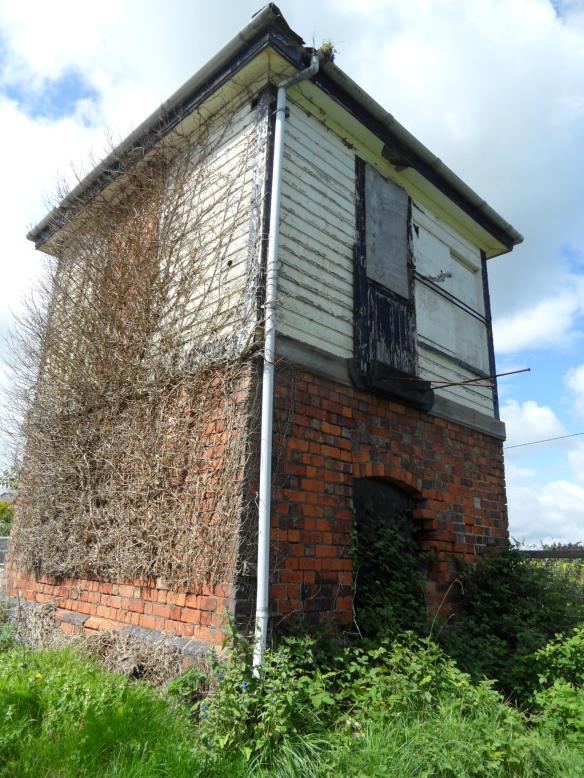

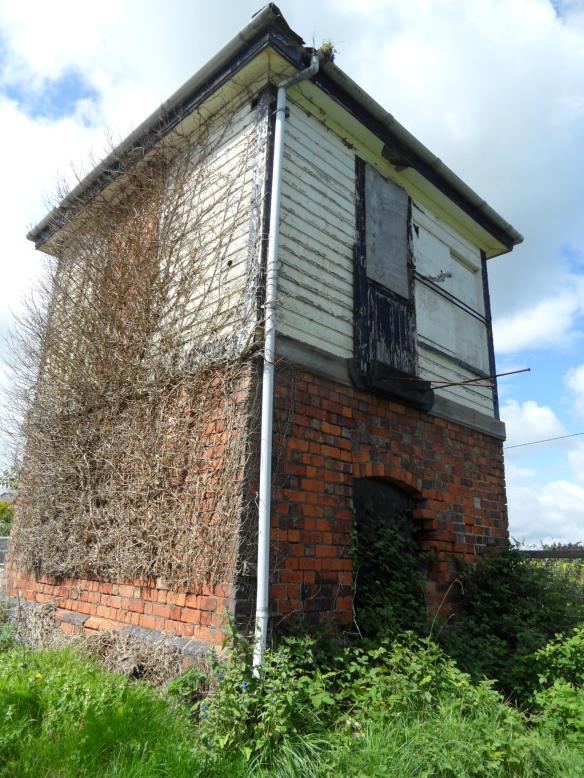

On the road back to Lichfield, down Claypit Lane I came across another relic of the railway. On the Fosseway Level Crossing is a signal box, built in 1875. Once again, I shall point you in the direction of the South Staffs rail site who have more information on this small but wonderful part of our history, and some photographs of the interior here. Also, there is a fantastic article on the South Staffs blog from a few years back, which I remember reading via Brownhills Bob’s blog, on Emily, who worked and lived at this crossing from 1946. You really should read it – it’s brilliant and it’s here.

I was just about to leave the crossing and carry on back to Lichfield down Claypit Lane when I saw this.

I’d heard about the trail via a talk that L&HCRT very kindly did for our Lichfield Discovered group, but hadn’t ever got around to finding it and now here it was! Once over the stile, the path takes you past what is left of this stretch of the Lichfield Canal.

As with the railway line, much of it has been reclaimed by Nature who has decided that if us humans aren’t going to use it, then she’ll have it back thank you very much. I don’t know much about wildlife and ecology, but even I can see that this corridor is an amazing habitat for all sorts of flora and fauna. What does remain of the canal itself is fascinating, and being able to see it like this, in all its emptiness, really made me realise what an epic task building these structures would have been. And how deep it was.

I finished the walk near to Waitrose, once again amazed and delighted at just how much history and beauty there is so close to home. I’m certainly going to do it again and I recommend that you do too – it’s an easy five miles walk and even I didn’t get lost!

Sources:

file:///C:/Users/Kate/Downloads/50e_App4-Archaeological_Desktop_Survey_By_On_Site_Archaeology_Lt%20(7).pdf

http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=304434