The ‘Heritage at Risk’ register for 2014 was published by English Heritage today. The Register includes grade I and II* listed buildings, grade II listed buildings in London, and all listed places of worship, scheduled monuments, registered parks and gardens, registered battlefields and protected wreck sites assessed as being at risk.

There are eight entries from around the Lichfield District this year, including scheduled monuments at Alrewas, Elford, Fradley and Streethay, the Fazeley and Bonehill conservation area and three buildings, namely, the Angel Croft Hotel on Beacon Street, the Manor House at Hamstall Ridware and the old church tower at St John’s in Shenstone.

The Angel Croft Hotel has been deemed ‘At Risk’ for many years, but there is now a glimmer of hope that Lichfield’s fallen Angel may be saved. This year’s entry notes that, ‘permission has been granted for conversion to apartments with an agreement to secure the repair of the gates and railings. Work should start in the summer’. Time will tell, but I really do hope that 2014 will be the last time that the Angel Croft appears on the register.

Whilst the plight of the decaying Angel Croft is well known in Lichfield, other local entries on the list may be less familiar, but no less worthy of salvation. Fazeley, according to Lichfield District Council, ‘represents a remarkably intact industrial community of the period 1790-1850. It contains all the principle building types necessary to sustain the community; terraced housing, mills, factories, a church, a chapel, public houses, a school and prestigious detached Georgian houses’. They go on to say that, ‘the waterways, pools and associated structures built by Robert Peel Snr are an important part of Fazeley’s industrial heritage and have archaeological significance. Their significance extends beyond just the immediate locality as they represent one of the most important water power systems dating from the early part of the Industrial Revolution. As a contrast to Fazeley’s industrial heritage, the appraisal tell us that, ‘the historic hamlet of Bonehill…. is an important remnant of the areas agricultural past and despite the developments of the twentieth century still retains a peaceful, rural feel. It has a direct association with the nationally renowned Peel family’.

Yesterday, Gareth Thomas, GIS Manager at Lichfield District Council, uploaded a number of photos from their archive to Flickr. It just so happens that alongside the reminiscence-tastic images of Lichfield shops and businesses, Gareth has uploaded a number of photographs of the conservation area at Fazeley and Bonehill, showing us just what is at risk here, hopefully inspiring us to pay a visit ourselves.

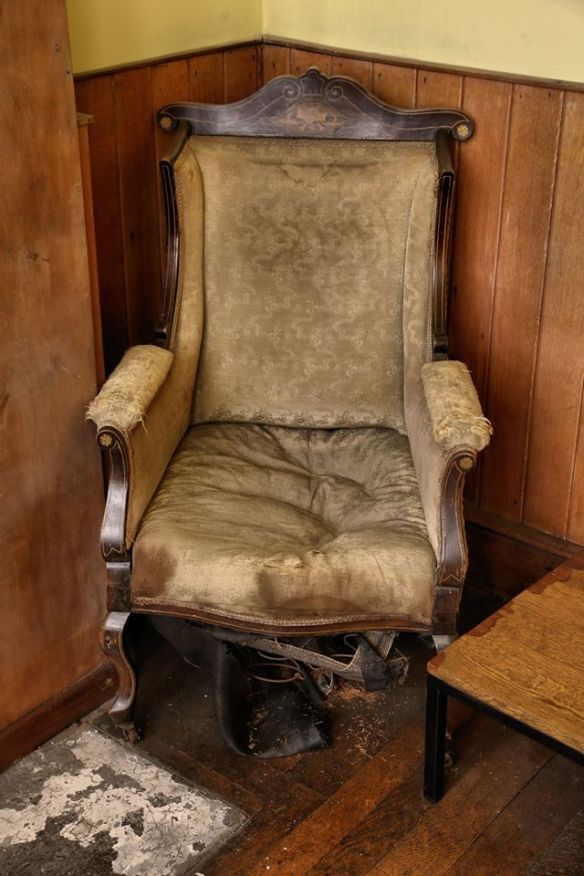

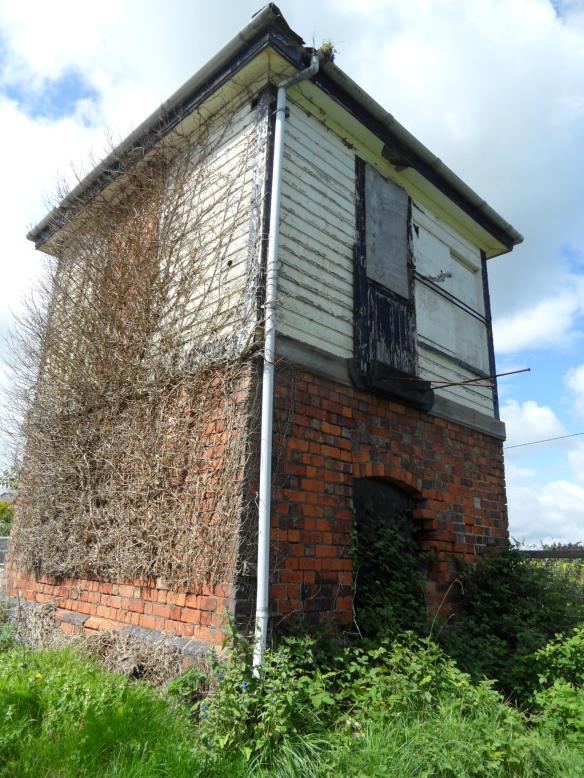

Also making an appearance in both the Lichfield District Council’s photo collection and on the ‘At Risk’ Register, is the Manor House at Hamstall Ridware. The pictures speak for themselves – the condition of watchtower is so bad that it is deemed at risk of collapse. Perhaps appropriately for something that may not be long for this world, I first caught sight of it from the churchyard of St Michael’s and All Angels and managed to find out a little about its history here.

Over in Shenstone, it seems there are ongoing discussions between the council, the Parish Council and the church regarding the old tower. At least for the time being, the structure is ‘considered stable’ – let’s hope that they all start singing from the same hymn sheet soon.

Same time, same places next year folks? Let’s hope not…

Thanks to Gareth Thomas and Lichfield District Council for the archived photos of Fazeley and Hamstall Ridware, and to Jason Kirkham for his photograph of the old tower of St John’s at Shenstone.