Throughout the year, the Lichfield Discovered group has hosted some fascinating talks on a range of subjects from symbolism in cemeteries (we never did find out about the mackerel!) to urban exploration and we’ve visited pubs, the Cathedral Close, Roman forts, pill boxes and tunnels. Before we hang up our boots and put the lid back on the biscuit tin for 2014, we have two more events coming up, which I want to let people know about.

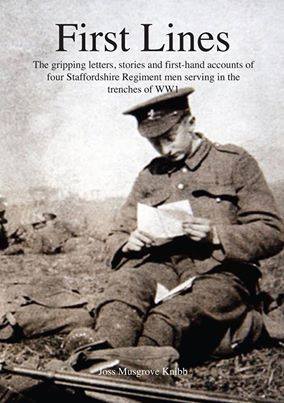

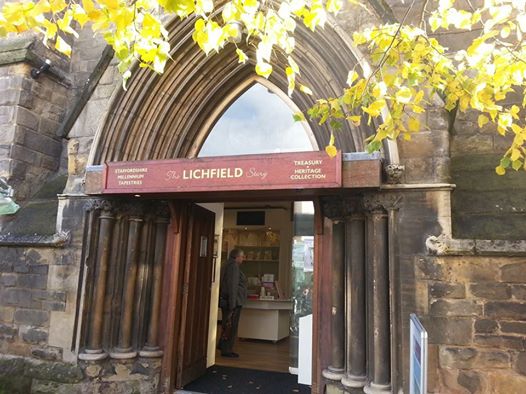

This coming Monday (10th November), we are delighted to welcome local author and journalist Joss Musgrove Knibb who will be taking a look at the previously unpublished letters of four Staffordshire Regiment soldiers who fought, and in some cases died, in the trenches of WW1. The vibrant letters of Alfred Bull of Lichfield, Sydney Norton of Tamworth, James Stevenson of Stoke-on-Trent and Jake Armes on the 1914 Christmas Truce bring the voices of these men vividly to life. With lots of photographs, stories and ‘trench humour’, it will be a thought provoking way of marking the centenary. The event takes place at 7pm at St Mary’s in the Market Square, Lichfield. There is no charge, but donations towards the centre are always appreciated.

The letters are part of Joss’ recently published book – First Lines. First Lines is published by Gazelle Press and is available to purchase across the region. Local outlets include WH Smiths (Three Spires Shopping Centre), St Mary’s Heritage Centre, The Cathedral Shop and the National Memorial Arboretum. First Lines retails at £9.99.

On Saturday 15th November we are meeting at the Guildhall at 2pm, where we’ll be exploring what remains of the city’s old gaol, first opened in 1548. After three hundred years, changes in the law meant that Lichfield’s prisoners were transported to Stafford after their trial, but a small number of cells were retained and used as the city lock-up. In 1847, the Inspector of Prisons visited the gaol and found that ‘the initials and names of many prisoners were cut deep into the wood work’. On our visit we’ll be attempting to locate and record this graffiti and have access to some of the cells which are not usually open to the public. Any names or initials that are discovered will then be compared with prison documents held by Lichfield Record Office at a later date. As it would be good to have an idea of numbers (it might get a bit cosy in those cells if there are too many of us!), please let me know if you would like to join us. We also need people to bring torches and cameras to help with the recording process.

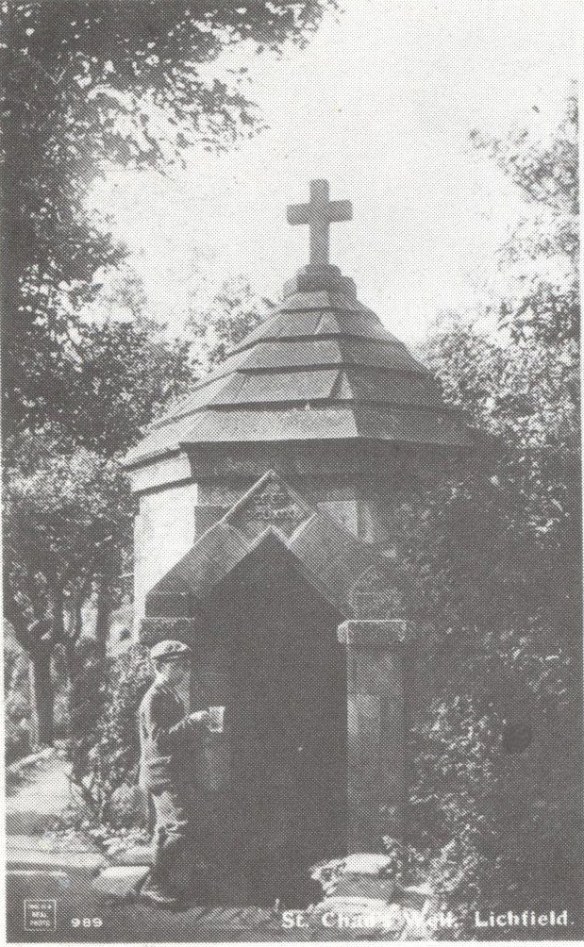

We’re currently working on next year’s programme of events for Lichfield Discovered but so far we’ve pencilled in a visit to the Spital Chapel – one of Tamworth’s oldest and loveliest buildings, a talk on Holy Wells of the Midlands, a visit to the timber framed Sinai Park House (where there’s also a holy well!) and closer to home, an exploration of Beacon Park and Beacon Street. As ever, we are open to suggestions and so if there’s anywhere you’d like to visit, or anything you’d like to know more about, tell us and we’ll see what we can do! Dates to follow, so watch this space. You can also keep up to date by following us on twitter @lichdiscovered or liking us on Facebook.

Spital Chapel of St James, Tamworth. During an archaeological dig in the latter half of the 20thc, to find any earlier structures on site, three skeletons were unexpectedly discovered in the area where the table is.