After reading that an inquest into a young boy’s death from drowning in the nearby canal at Sandfields in 1884 had been held at the Three Tuns Inn on the Walsall Road, I wanted to know more about the use of pubs in these circumstances.

The Three Tuns Inn, Walsall Rd, Lichfield, formerly Panache Restaurant & currently being developed

I had a look at the newspaper archive and found another report in the Lichfield Mercury, this time from December 1885, regarding the death of a soldier who had been found in the Birmingham Canal near Quarry Lodge. After being discovered, the body was taken to the Shoulder of Mutton in a cart on a Monday afternoon, where it was examined by Brigade Surgeon G Simon M.D. The following evening Mr C Simpson, the City Coroner, held an inquest into the death where a verdict of ‘drowned’ was returned by the jury.

I understand that this was how things were done all across the country. I think I’m right in saying that until the Public Health Act of 1875, there were no public mortuaries and in the event of a sudden or unnatural death, inquests were held at a nearby public building, often an inn or public house. If a body was discovered outdoors, the pub would also become a temporary mortuary.

On Google books, I found a document from 1840 detailing Coroners’ Reports for England and Wales. The Lichfield Coroner at the time, Mr Simpson, submitted a return giving the number of inquests held in Lichfield in each of the years between 1834 and 1839, together with a schedule of allowances and disbursements to be paid by the Coroner, as follows:

To the bailiff of the court for summoning the jury and witnesses attendances on the coroner and at the inquest: 5 shilling

To the witnesses not exceeding per day (besides travelling expenses): 3 shilling

For the jury, each juror: 1 shilling

For the use of the room: 5 shilling

The returns submitted by Coroners vary from place to place in the amount of detail included. For example, the return for Ripon outlines further payments made, including 5 shillings paid per day, ‘to expenses of room and trouble, where dead body is deposited till inquest held’, and ‘to the crier of any township for crying when body found and not known’. The return of Mr H Smith, the Coroner for Walsall, gives names of the deceased and the dates on which the inquests were held. In Leicester, John Gregory recorded the number of inquests in the four years ending August 1839 and added an explanatory note that the increase in inquests in the last year was mostly due to accidents occurring in the formation of the Midlands County Railway through the county. In a handful of towns, the Coroner also recorded the verdict (e.g. accidental, visitation of God, wilful murder) of the inquest. It doesn’t make for pleasant reading, but it’s a fascinating and important document for local or family historians.

By the late nineteenth century, things began to change. As previously mentioned, the Public Health Act 1875 gave permission for local authorities to provide public mortuaries and in the early twentieth century, The Licensing Act of 1902 stated that:

From and after the thirty-first day of March one thousand

nine hundred and seven, no meeting of justices in petty or special

sessions shall be held in premises licensed for the sale of intoxicating

liquors, or in any room, whether licensed or not, in any

building licensed for the sale of intoxicating liquors ; nor shall

any coroner’s inquest be held on such licensed premises where

other suitable premises have been provided for such inquest.

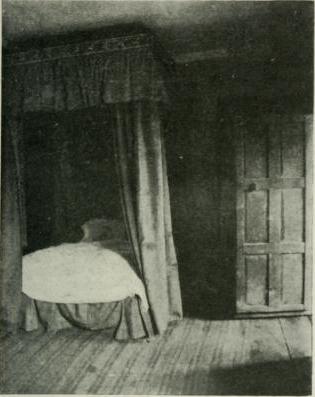

Yet at this time in Lichfield, there was no suitable premises, as can be seen from a further report in the Lichfield Mercury on 24th April 1903, regarding an inquest into the death of a woman in Old Sandford St. The inquest was held at the nearby Hen and Chickens pub, although the post mortem was carried out by Dr F M Rowland at the deceased’s address, as her body had been discovered at home in bed. At the inquest, the coroner, S W Morgan commented on the situation, stating that it was a case that should have been taken to a mortuary. The room was nine or ten feet square, with a window right down to the floor. The double bed in the room had to be taken out and a table brought in. All of the utensils had to be borrowed, as there was nothing in the house that could be used. The Foreman of the Jury, a Mr Cooney, was reported as saying it was ‘disgraceful’. He considered it a scandal that there wasn’t a mortuary, though he was under the impression that one had been built in the city over at the council property on Stowe Street. With the rest of the jury sounding their agreement, the Coroner added,

“I called the attention of the council to this matter…12 or 18 months ago, when a recommendation was passed by a Jury. It is astonishing that the City of Lichfield does not possess a mortuary, when one takes into consideration the fact that there are two stations in the place, and how frequently people meet with fatal accidents on the railway. It is most unfair that publicans should be called upon to take in these cases, and it is unfair to ask them to do it. Suppose a tramp happened to die, whilst passing through the town, that man, unless some kind publican happened to take him would have to be hawked around from public house to public house, until someone consented to take the body. It is simply a scandal and a disgrace that such a state of things should exist especially when a mortuary could be built at a small cost”.

Dr Rowland added that there had been plans for a mortuary, but they had been shelved, to which the Coroner replied, ‘It is not fair to the medical gentlemen to ask them to make the post-mortem examination under such conditions’. The Jury recorded a verdict of ‘Death from Natural Causes’, and added to it a rider calling on the City Council to proceed with the erection of a mortuary.

In May 1903, the body of a man was found on the railway line at Shortbutts Lane. The Duke of Wellington refused to admit the body, but the landlord of the Marquis of Anglesey allowed his stable to be used. The Coroner commented that it was as if the fates were conspiring to emphasise the need for a public mortuary in Lichfield. By June that year, plans to convert one of the storerooms at the Stowe Street Depot had been put forward amidst concerns by some members of the council that a scheme to erect a purpose built mortuary in the city was too costly. By August, discussions over the expense were continuing. Councillor Johnson claimed he was in favour of a mortuary but not wasting money on it. Councillor Raby replied by saying that the City had been brought into oppobrium enough through not having a mortuary, and that ‘the ghost of obstruction which Mr Johnson had conjured up should be buried’.

Finally, in November 1903, the Surveyor reported that the Stowe Street mortuary had been completed at a cost of £48 9s 5d. Exactly a year later, the City Council’s attention was drawn to the fact that dead bodies covered in sheets could be seen from Stowe Pool Walk. It was agreed that a blind should be installed and lowered when the mortuary was occupied, an almost symbolic drawing of the veil between those living in this world and those who had joined the next. Death in Lichfield was no longer in the public eye.