This Christmas, for the first time ever, I watched the Queen’s Speech. I’d read somewhere that there had been a flurry of bets on the Queen abdicating and though sceptical, I interrupted a FIFA match between Walsall and Barcelona to seize momentary control of the television just in case. Of course, it had been nothing but a rumour and Charles remains a king in waiting.

Earlier that week, I’d been to visit a house associated with another King Charles to be. Following defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3rd September 1651, Charles Stuart had fled north to Shropshire, hoping to sneak across the border into Wales and sail from there to Europe. The Parliamentarians were one step ahead of him and were closely guarding the River Severn crossing places and ferries, thwarting this plan. In the early hours of 8th September 1651, Charles arrived at Moseley Old Hall in Staffordshire, looking for a place to hide and a new escape route. He was met at the back door by owner Thomas Whitgreave and the family priest John Huddleston (1), who gave up his four poster bed (2) and shared his hiding place with the future King when Cromwell’s soldiers came seeking him.

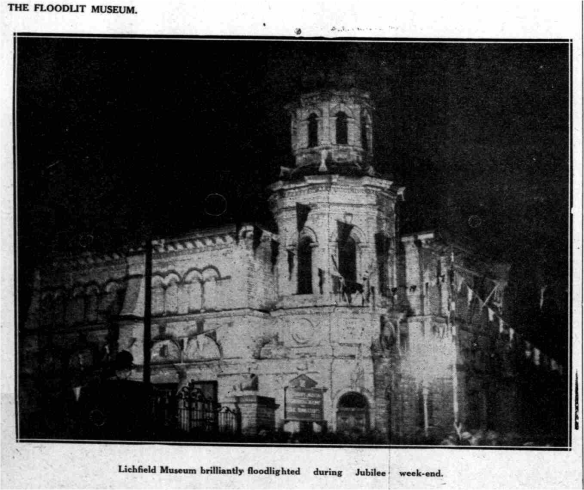

Moseley Old Hall as it was…. taken from ‘The Flight of the King by Allan Fea (1908)

….and as it is today. Well, last Sunday anyway.

The house which hid the King is now hidden itself behind a Victorian redbrick facade. As we waited outside, making jokes about standing under the mistletoe, the guide informed us that we were about to enter the hall through the very same door as the King had, and told the assembled children to let their teachers know about it. Mine were only here because I’d promised they’d be able to toast some bread over an open fire at the end but they seemed suitably impressed (3). One little lad wanted to know if there was going to be a ride. I suppose in a way there was.

The back door through which Charles entered Moseley Old Hall on 8th September 1651

As everyone knows (4), before the King came to lie low at Moseley he’d been hiding high at Boscobel, nine miles away on the Staffordshire/Shropshire border. A tree house inspired by the Royal Oak, the most famous of all the places the King found refuge, is a recent addition to the King’s Wood at Moseley. There are signs warning of peril, and whilst the element of danger here is not quite on a par with that of a man with a thousand pound bounty on his head hiding in a tree, it’s enough to get overprotective parents like me muttering, ‘Be careful!’, as if it were a charm to invoke protection.

The Moseley Old Hall Tree Hide

The Royal Oak in 2011, Boscobel House, Shropshire

Uploaded to Wikipedia in May 2011 Sjwells53 CC BY-SA 3.0

I’ve yet to visit Boscobel, owned by English Heritage. I understand that today’s Royal Oak grew from an acorn of the original tree which was destroyed by visitors in the seventeenth century who, in the absence of a gift shop, took away branches and boughs to fashion into souvenirs. In his book ‘Boscobel’, Thomas Blount described,

‘this tree was divided into more parts by Royalists than

perhaps any oak of the same size ever was, each man

thinking himself happy if he could produce a tobacco

stopper, box etc made of the wood.’

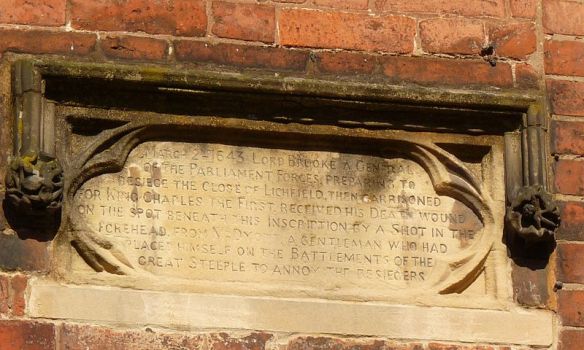

These trinkets still turn up at auctions. In 2012, a snuff box sold at Bonhams for almost £7,000. Another prized relic at the time of Charles’ great escape was a rag he’d used to mop up a nosebleed. Father Huddleston passed this ‘bloody clout’ to a Mrs Braithwaite who kept it as a remedy for the King’s Evil, another name given to the disease known as scrofula. Since the reign of Edward the Confessor, it had been thought that the disease could be cured by a touch from a King or Queen. Of all the royal touchers, Charles II was the most prolific. The British Numismatic Society estimate he touched over 100,000 people during his reign. The tradition was continued, somewhat reluctantly, by King James II who carried out a ‘touching’ ceremony at Lichfield Cathedral in 1687 (5). The last English Monarch to partake in the ritual was Queen Anne, who ‘touched’ a two year old Samuel Johnson at one of the ceremonies in 1712. The touch piece or coin which the Queen presented young Samuel with, which he is said to have worn throughout his life, is now in the British Museum.

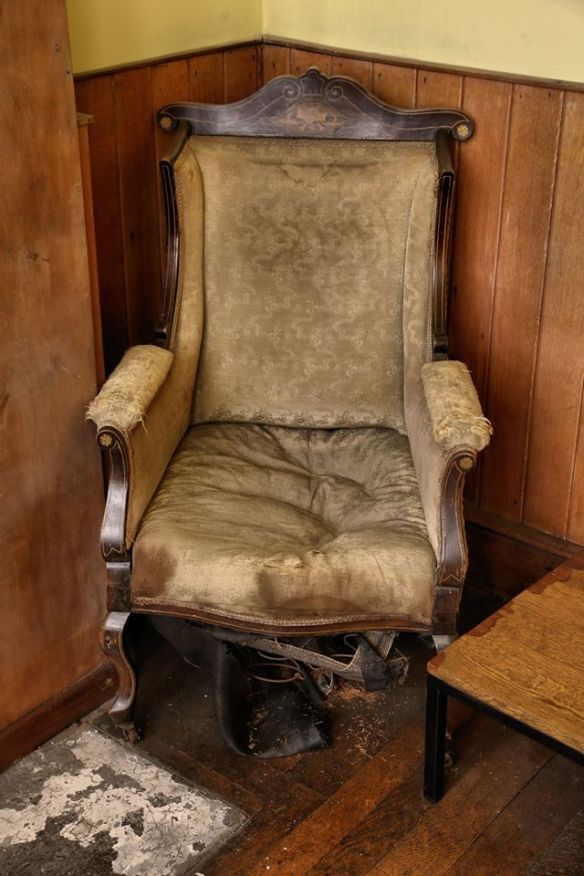

John Huddleston’s room now known as the King’s Bedroom from The Flight of the King by Allan Des (1908)

By the mid twentieth century, Moseley Old Hall was suffering from neglect and subsidence. This ‘atmospheric Elizabethan farmhouse that saved a King‘ was itself saved by the National Trust, when they took over in 1962. Every year, thousands of people pass through that door to see that bed and hiding place. Seems that three hundred years on the King hasn’t lost his touch. Or maybe they are just here for the toast?

Notes

(1) As the king lay dying in February 1684, Huddleston was said to have been brought to his bedside with the words, “This good man once saved your life. Now he comes to save your soul”.

(2) The bed at Moseley is the original one the King slept on top of. It was bought by Sir Geoffrey Mander of Wightwick Manor in 1913, but was returned to the hall in 1962 by his widow, Lady Mander.

(3) It seems the King’s victory was only short-lived. One of them just asked what I was writing about and when I told them it was Moseley Old Hall they replied, ‘Oh yes, the place with the toast’.

(4) If you didn’t know, take a look at this great map from englishcivilwar.org which plots all of the stages on the King’s journey from the Battle of Worcester to his arrival in Fécamp, France

(5) More information can be found in ‘Touching for the King’s Evil: James II at Lichfield in 1687’, in Volume 20 of the The Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society transactions.

Sources:

Moseley Old Hall, National Trust Guidebook

Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions Volume XL

http://www.coinbooks.org/esylum_v17n40a13.html

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/cm/d/dr_johnsons_touch-piece.aspx