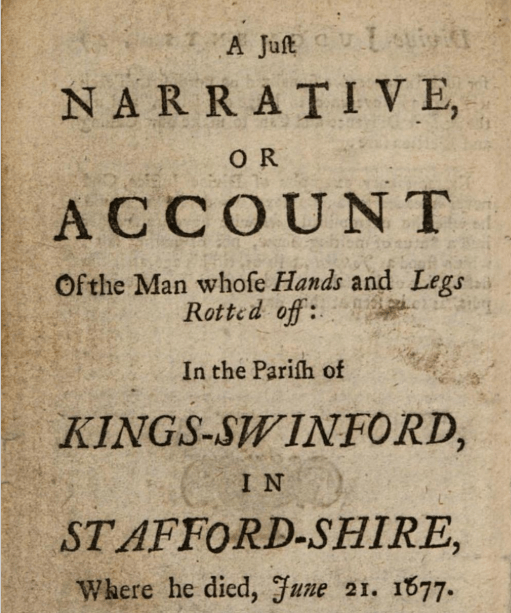

When John Duncalf was released from the House of Correction in Kingswinford in 1675, he swore he would never set his feet in the town again as long as he lived. It was a promise that was to become grimly prophetic.

On leaving Kingswinford, he embarked on a life of petty crime and sin. He would later confess to, ‘Idleness, Stealing, Cursing, Swearing, Drunkeness and Uncleanness with Women’, although he explained that he had not actually committed actual Fornication or Adultery with a woman except in the thoughts of his heart, and by lascivious words and gestures, whereby he had endeavoured to tempt them to lewdness in divers places. I think we can infer from this that his lack of lewd action was not for want of trying.

The chapter of crime he was to become truly infamous for was the theft of a bible. If he’d only read one of them, paying particular attention to the eight commandment, things could have turned out a lot differently. But, on 5th January 1677, Duncalf turned up on the doorstep of Grange Mill, masquerading as a beggar. It was the home of Margaret Babb and when she charitably invited him in for a drink to celebrate Twelfth Night, the bad man stole her good book.

Duncalf sold Babb’s Bible on to a maid at Heath Forge at Wombourne but its provenance was discovered and suspicion fell on Duncalf. He swore it wasn’t him apparently, ‘wishing his hands might rot off, if that were true’. It would turn out to be the second prescient statement Duncalf would make. Soon afterwards, the flesh around his wrists began to turn black. His ungodly wish was about to be granted.

A few weeks later, Duncalf was working in Dudley with a joiner called Thomas Osborn when he felt weak and faint and feverish. It was Shrove Tuesday and he headed home towards Codsall but collapsed in a barn at Perton Hall in Tettenhall en-route. After two days and two nights, he was discovered unable to walk and so was carried back to his last place of settlement. And so it was that John Duncalf found himself back in the town of Kingswinford but, just as he had sworn, without actually set foot in the place. He was taken in by a man called John Bennett and at first he was lodged in a barn belonging to the Three Crowns Inn on the Wolverhampton to Kidderminster Road. After a fortnight, he was taken to Bennett’s house in Wall Heath where his blackened flesh began to rise in lumps at his hands and wrists before beginning to decay.

The account I’ve read comes from James Illingworth, one of the clergymen who visited him amidst the crowds. He says that by the end of April, ‘many little Worms came out of the rotten flesh, such as are usually seen in the dead Corpes (sic)’. Many visitors also appeared, posies pressed to their nostrils to block out the putrid smell, hoping to see the man who they believed was being literally and directly punished by God for his sins. Despite everything, Duncalf did not appear to have learned his lesson. Illingworth heard him tell his keeper John Bennet that he wished his visitors’ noses might drop off and asked why he did not dash out their teeth to stop them from grinning at him.

Eventually, Duncalf asked for Margaret Babb to visit, and she came with the maid he had sold the stolen book to. He confessed his crime to them and asked their forgiveness, which both of them granted. When his hands rotted off, there was hope that penance had now been paid and that God would punish him no more. Yet, the suffering continued. By 8th May, both of his lower legs had fallen off at the knee, although he didn’t realise it until Bennett held them up to show him.

According to the Dudley Archives and Local History Service, the entry in the parish register at Kingswinford shows that John Duncalf was buried on 22nd June 1677, and is described as, ‘the man that did rott both hands & leggs’. The entry notes that he stole a bible, a charge, ‘he wickedly denyed with an imprecation, wishing that if he stole it his hands might rot of which afterwards they did in a miserable manner’. It adds that, ‘many people (I verily believe hundreds) saw him as hee lay with his hands & leggs rotting off, being a sad spectacle of God’s justice and anger’ and ends by saying it was registered as, ‘a certain trueth, to give warning to posterity to beware/ of false oathes’.

Clearly there is a certain trueth to this story which elevates the death of John Duncalf to more than mere folklore but what did cause his terrible demise if it wasn’t a punishment dished out via divine judgement?

A memorial in the tower (which you can see here around 13m20s in) and an entry in the parish register at the now disused church of St Nicholas at Wattisham in Suffolk describe the sad fate of the Downing family who all lost their feet in 1762, although four of them survived. I’ll spare you from the full gory details but belief amongst local people was that the poor family were victims of witchcraft. The local vicar Rev Bones (I kid you not) was not convinced and set out to ascertain the cause of their affliction sending several letters to the Royal Society who concluded the culprit was gangrenous ergotism caused by eating grains infected by the fungus Claviceps purpurea.

I’ve seen this ‘tragic ‘singular calamity’ as Rev Bones called it, described as the only recorded case of ergot poisoning in England. However, I strongly suspect that John Duncalf may have been another of its victims and possibly, had John Bennett and others sought medical attention for him rather than condemning him to be some sort of religious freak-show, he may even have survived.

I definitely wouldn’t swear on it though…

Sources

Ian Atherton (2022): ‘John Duncalf the Man that Did Rott Both Hands & Leggs’: Chronicle of a Staffordshire Death Retold in the Long Eighteenth Century, Midland History, DOI: 10.1080/0047729X.2022.2126237

Divine Judgements Exemplified

https://www.facebook.com/dudleyarchives

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/uh33ekuf

Hereford Times – Saturday 09 March 1867