I pass by the Clock Tower at the Friary several times a week and in the stillness of the night, I can hear it chime, slightly out of synch with the Christ Church clock. According to Annette Rubery‘s wonderful new book, Lichfield Now and Then, the tower was built in 1863 to mark the 300th anniversary of the Conduit Lands Trust. When the new Friary Rd was built, the tower was moved to its present location. The Wikipedia entry here has some photos of it in its original site at the junction of Bird St and Bore St. The Staffordshire Past Track has some great photos of the tower being dismantled, including one of the bells being lowered down (is this one of those I can hear?).

The tower was originally built over the site of an ancient water conduit, known as the Crucifix conduit. Some say this name came from a crucifix on top, others say it derived from its location near to The Friary. Back in 1865*, someone called CW wrote in to ‘Notes and Queries’ (a publication resembling a magazine, but actually sold under the description of ‘A Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, General Readers, etc’!) on the subject:

At Lichfield is a structure The Crucifix Conduit. It has been rebuilt within the last few years and now there is a plain cross on the top. Did the original have a crucifix? Was the crucifix, if any, destroyed in Puritan times? Is there any drawing of the building in existence And if so where can see it?

A literary man (or possibly a general reader!) replied as follows:

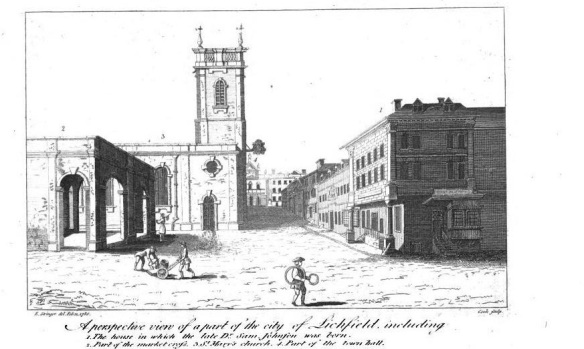

The old conduit at the Friary gate does not appear have been surmounted with a crucifix but was so called from Crucifix being the name of the locality on which stood. Gregorius Stoneing receiver of the rents of possessions of the Fryars Minors of Lichfield after dissolution thereof in his account in the court of Augmentation answered, and so was charged with, and the rent of a certain water course within the compass circuit of the late house of Fryars aforesaid running from Poolefurlonge to Lichfield street, viz to a certain called the Crucifix demised to John Weston at the will of the Lord. (Shaw’s Staffordshire 1820) A engraving of the old crucifix conduit will be found A Short Account of the Ancient and Modern State Lichfield 1819′.

A quick search on the invaluable googlebooks finds that book, and as promised, a drawing of the crucifix as it looked in 1819.

I had thought that the Crucifix conduit was no longer in use by the time the clock tower was built – the listed building description says it was built over the ‘redundant conduit’. However, different accounts suggest that the conduit was still used as a public water supply beyond this date. The County History says ‘In 1863 it (the Crucifix Conduit) was adapted as the base of a clock tower designed in a Romanesque style by Joseph Potter the younger, but the conduit continued in use’.This probably explains why what look like drinking fountains can be seen built into this section of the tower!

I find this next bit confusing and am happy to be corrected! What I understand is that the water came from a spring at Aldershaw. In 1301, Henry Bellfounder granted the Fransican monks the right to built a conduit head over the spring, and to pipe the water to the Friary. He apparently did this for motives of charity and for the sake of his and his ancestors’ souls’ health. Although it seems the water was supposed to be for the friars’ use only, a public conduit was built outside the Friary gates. When the Friary was dissolved in the mid-16th century, I understand that the Conduit Lands Trust took over the responsibility for maintaining the water supply to Lichfield when the spring at Aldershaw was granted to the ‘Burgesses, Citizens and Commonalty’ of the City of Lichfield. A fountain marks the approximate site of the original public conduit (and of course the later clock tower) near to the library and record office. Although the water is no longer suitable for drinking, it serves as a symbolic reminder of the water supply that was once available here.

A stone conduit head dating back to 1811 can apparently still be found over the spring at Aldershaw. The spring was known as Foulwell which may not sound like the most appealing place to get water from, but as BrownhillsBob explained to me that the name ‘foul’ is most likely to mean ‘obstructed’ in this context. What’s also interesting is that the well seems to have an alternative name – Donniwell, which crops up in some transcriptions of old documents (dating back to the 4th year of the reign of Edward VI which would be 1551. I think.) that Thomas Harwood made in 1806.

Funnily enough, searching to find an interpretation of the name lead me back to another edition of ‘Notes and Queries’, (this earlier issue from 1855 was described as a ‘Medium of Inter-Communication between for Literary Men AND Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists etc). Someone else had questioned the meaning of Donniwell in relation to the spring near Lichdfield, and received the following answer from WLN of Bath.

The word Donni or Donny in Donniwell is merely the old Keltic (sic) vocable don (otherwise on or an), water, with the diminutive y, and signifies the little stream or brook The word is still retained in the name of the rivers Don in Yorkshire, the Don which falls into the sea at Aberdeen, another Don in county Antrim Ireland, and in the Don in Russia. Hence, too, the Keltic name for the Danube, Donau, latinised Danubius. There is also Donnyland in Essex and the two rivers Oney in Salop and Herts, Honiton or Onyton in Devon and the Uny in Cornwall are all different forms of the same root.

I might offer many other illustrations but will refer only to the same word in the primitive nomenclature of Palestine the Dan which, with the later Hebrew prefix Jor (river) we now by a double pleonasm, call the river Jordan

So there’s one idea…..anyone have any other ideas of where this name may have derived from?

Coincidentally yet appropriately, today is the 8th December, the Feast of the Conception of St. Mary, the date on which two wardens were appointed each year to keep the conduits and watercourses of Lichfield’s water supply in repair. I also like the idea that the chiming bells of the Clock Tower provide an appropriate, yet coincidental link to the name and occupation of the man who originally gave the spring at Aldershaw which fed the conduit (at least I think its coincidental….). I also find it interesting that back in the mid 19th century people were asking similar questions to the ones that I’m asking today. It seems it’s not just me that is fascinated by the idea of springs, wells, conduits and water in general!

Coincidentally yet appropriately, today is the 8th December, the Feast of the Conception of St. Mary, the date on which two wardens were appointed each year to keep the conduits and watercourses of Lichfield’s water supply in repair. I also like the idea that the chiming bells of the Clock Tower provide an appropriate, yet coincidental link to the name and occupation of the man who originally gave the spring at Aldershaw which fed the conduit (at least I think its coincidental….). I also find it interesting that back in the mid 19th century people were asking similar questions to the ones that I’m asking today. It seems it’s not just me that is fascinated by the idea of springs, wells, conduits and water in general!

Now I know a little more about where the water came from, and where it went to, I’d like to know more the inbetween part i.e. the actual route of the water. That also goes for the conduit between Pipe Hill and the Cathedral Close too. As it looks unlikely that I’ll be able to go looking for the conduit head at Aldershaw (it’s on private property) as I did with the one at at Pipe Hill, I shall have to concentrate instead on tracking down the archaeology reports and journals that reveal more about our medieval conduits, at Lichfield Record Office.

Also, for more about the Friary, Gareth Thomas has added some original deeds and plans to his blog All About Lichfield.

*This date is a little strange as the Clock Tower was built in 1863. Perhaps the letter was written before this time and not published until 1865.

Edit: 10/12/12

I’ve just been reading part of The History of the South Staffordshire Water Works Company. This suggests that a public water conduit of some description, pre-dates the granting of the spring at Aldershaw to the Friars. Apparently, there was a public conduit in the early 13thc, and there are also references in the Cathedral records to a Conduit St, and a conduit in the high street. Are these are connected to the Crucifix conduit or separate? And where did this water come from?

The document also gives some really interesting information on the pipes themselves. It says that originally wooden pipes were used (bored tree trunks). It refers to a document from 1707, that says the pipes ‘being made of alder had become rotten, leaky and in decay and accordingly taken up and replaced by leaden pipes’. Interesting that the pipes were made of Alder, and the water came from Aldershaw. It also says that in 1801, the Conduit Lands Trust replaced a small gauge lead conduit from Aldershaw with a larger diameter cast iron main, which enabled a greater volume of water to be carried to the City. It also gives this interesting information on what happened when supply started to exceed demand.

By 1821, Aldershaw was proving to be inadequate source and a scheme was devised to supplement the spring’s supply, by collecting the surface water from Tunstalls Pool, the Moggs and other pools and diverting water into the common conduits. When the situation worsened in the mid 1850’s, the trustees acquired the Trunkfield Mill and Reservoir and a pumping engine was installed to increase the supply. In 1868 the supply of Aldershaw yielded 15,000 gallons a day. Trunkfield supplied 160,000 gallons a day, all of which was pumped to Crucifix Conduit. Water was provided to fifty seven public pumps, thirteen standpipes and public taps, thirty fire hydrants and three hundred and forty three houses.

The document isn’t too specific about their sources, so having to take what they say on face value for now. Lots more reading to do I think….Luckily for me, local historian Clive Roberts is going to send me some information he has on the Conduit Lands Trust!

Sources:

Lichfield Then and Now Annette Rubery

A short account of the city and close of Lichfield by Thomas George Lomax, John Chappel Woodhouse, William Newling

The History & Antiquities of the City of Lichfield by Thomas Harwood (1806)

Lichfield: Public services’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield(1990), pp. 95-109

Water Technology in the Middle Ages: Cities, Monasteries, and Waterworks after the Roman Empire by Roberta J Magnusson

Walsall Road, Lichfield, Staffordshire. A Report on an Archaeological Evaluation

Marches Archaeology Lyonshall : Marches Archaeology, 2000, 18pp, figs, tabs

Work undertaken by: Marches Archaeology

History of the city and cathedral of Lichfield by John Jackson

Notes and Queries 12th Volume 1855

Notes and Queries 3rd Series Volume 8, 1865