Since visiting the new Christian Fields local nature reserve last year, I’d been waiting for an opportunity to return and follow the ancient route which runs from the reserve to the village of Elmhurst.

I was eager to see was whether the dry pool/well we thought we’d found last time had filled with water. Turns out it had, but not necessarily in the way I was expecting… When I went in September it looked like this:

Now (assuming I have got the right place!) it looks like this:

The reason for the change is that site is being developed with £100,000 of funding to attract wildlife (and members of the public!) to the site. As well as the new pond and dipping platform, there will also be picnic areas, wild flower meadows and information boards. There were lots of tadpoles swimming about in the new pool, so it looks as though efforts to improve the site’s biodiversity may be starting to pay off. You can read more information on the project here.

After watching the tadpoles, we passed two women out dog walking.One was trying to disentangle herself from a bramble that had taken a liking to her, but it seemed the feeling wasn’t mutual. “Bloody nature!”, we heard her shout as we walked past.

We continued along the wooded path leading to Fox Lane, Elmhurst. Interestingly, up until the middle of the last century, it seems that both the path and Fox Lane were actually a continuation of Dimbles Lane. After brushing past wild flowers and negotiating tree roots on the narrow, winding path we emerged from the green corridor into the village. I would love to know how often this path was trod by past generations, but surely none of them have ever tried to take a motor vehicle up there. Have they?

I believe that ‘new’ name for the lane relates to a retired business man, George Fox, who bought Elmhurst Hall in 1875. Fox died in London from a chill in 1894 after moving from Elmhurst to enable the Duke of Sutherland to use the house to host the Prince of Wales on his visit Lichfield for the centenary of the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

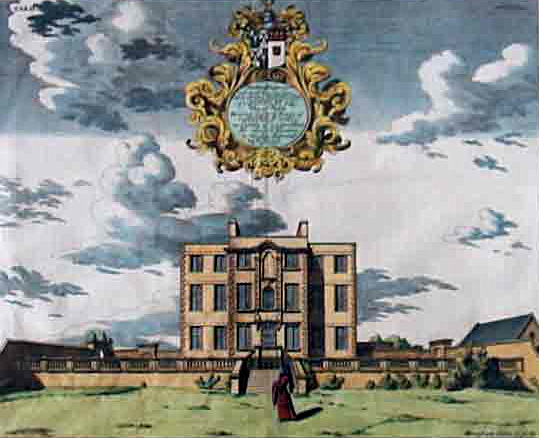

The original Elmhurst Hall was built by the Biddulph family in the late seventeenth century and replaced by an Elizabethan style house in 1804, with building materials from the original house being offered for sale. I wonder where these parts of Elmhurst Hall ended up?

Source: Wikimedia commons

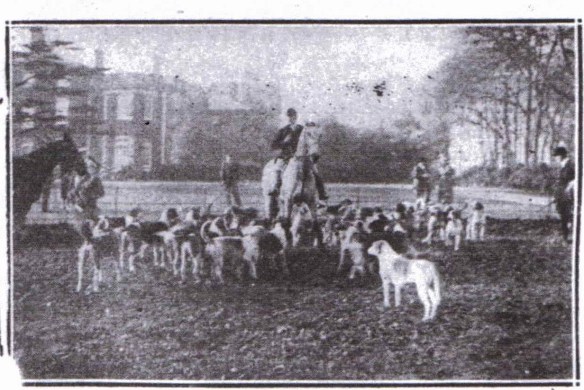

Source: Wikimedia commons

The second Elmhurst Hall was demolished in 1921. Its last owner was the brewer Henry Mitchell (as in Mitchells & Butlers). There are still remains of the estate in evidence including a walled garden which dates back to at least 1740 and a lodge built in the 1870s, in the same style as the main hall, known as High Field Lodge. There was also another earlier lodge on Tewnals Lane but I haven’t been to have a look and see if that still exists.

High Field Lodge

Walled Garden

Whilst at Elmhurst Hall, Mr Fox established a mission room linked to St Chad’s Church, Lichfield to compensate for a lack of a place of worship in the village. I understand that services were taken by students from Lichfield Theological College and Mr Fox himself.

Wild garlic & a rusty barrow outside the Mission Room

As I was walking, I couldn’t help but think of Alfred Cleveley, a butler a Elmhurst Hall in 1914 and later a recipient of the Military Medal, killed in action in May 1917, who I wrote about here. I later found that Private Joseph Hall, aged 20 and a member of the Mission Room choir also lost his life during the war. Born in Elmhurst in 1897, on the 1911 census Joseph was an errand boy. It’s a sad thought that the names of Joseph and so many like him would not appear on another census but instead on war memorials and rolls of honour. However, there did seem to be some controversy regarding where names should be included. Whilst reading through the newspaper archive on Elmhurst, I found a letter from someone using the pseudonym ‘A Mother’, wanting to know why her son, born at Elmhurst, who died making ‘the great sacrifice’ on the battlefield aged just eighteen years old, should not be eligible to have his name enrolled on the Lichfield memorial. Apparently, she was told after making a voluntary subscription that the lad did not belong to Lichfield. ‘Then where did he belong to I should like to know?’ ends her letter.

I imagine that both Joseph Hall and the unnamed soldier went to Elmhurst School, opened in 1883 on land given by George Fox who also sat on the board as chairman. A proposal to close the school on account of low numbers was rejected by parents in the 1930s, and the school remained open until 1980 when the building was taken over by the Elmhurst and Curborough Community Association and pupils were transferred to other Lichfield primary schools, including Christ Church.

The Lichfield side of Dimbles Lane now has a very different feel to the rest of the route which shares its name, although the former landscape is reflected in the names of some of the new closes and crescents built by the local authorities after the First World War and throughout the twentieth century – Bloomfield, Greencroft, Willowtree. The building program meant that the population of Lichfield increased significantly, and it’s a good reminder that housing estates are just as much a part of our history as the old country estates such as Elmhurst Hall. This is something that is being recognised more and more these days with some great work on our recent past going on in other places. For now, I will try and put something together so that others can follow this walk for themselves.

Start of Dimbles Lane at the Lichfield city end

Dimbles Lane as it crosses Eastern Avenue and enters Christian Fields Nature Reserve

Edit: Oh look! There’s a story here on Lichfield Live about volunteering at Christian Fields LNR on June 3rd. If you go, say hi to the tadpoles for me!

Sources:

Townships: Curborough and Elmshurst’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 229-237

Lichfield Mercury Archive