Recently, twelve year old Lily made a very interesting discovery in Lichfield. Here’s her account of how the contents of a cardboard box found in an old gaol cell turned out to be far more exciting than than anyone could have imagined….

“In November 2014, I went to the Lichfield Gaol Cells in the Guildhall. It was a Lichfield Discovered event, and we were going to look and see if we could find any graffiti, names, or dates on the gaol cell doors. About 7 or 8 of us came to the event all in all, I came with my Dad. Everyone else managed to find lots of writing and names on the doors, I didn’t find much. Near the end of the session, we were looking inside the third jail cell, the one that is not normally open to the public. My Dad pointed out 2 boxes of old looking tiles on the floor, we took a quick look, but we didn’t pay much attention to them.

The next time we came to the gaol cells was on 21st February, we had come back to see if there was any more graffiti that we had missed, also to take a second look at the boxes of tiles (Jo at the museum said it was ok). This time I had come with my Mom and there was around 8 people that turned up this time. Me and my Mom started looking through the tiles, we had picked about 5 up and we laid them on a chair to photograph them, but they werereally dusty so we couldn’t see if there were any other patterns on them.

There were so many tiles that we couldn’t fit any more on, we decided to move all of the tiles into the 4th cell, onto a wooden bed that the prisoners used to sleep in, (personally I would NEVER think of sleeping on one of them). We started taking some more tiles out of the box and moving them onto the bed. We moved them a few at a time, because the box was too heavy to lift. I had realised that there were a few tiles with the same pattern on. I really wanted to get a better look at what the patterns looked like, so my mom went to Wilko (just up the road) to buy 2 paintbrushes. When she got back we started brushing off the dust and dirt from the tiles we had got out, we could see the patterns a lot clearer. We had nearly finished emptying out the first box of tiles, and at the bottom my Mom found a bit of tile with ‘Lichfield Friary’ written on the back. She showed it to Kate and she said “Maybe it came from the old Friary!” and then we all got really excited!

We had found lots of bone shaped tiles that were exactly like the one that said ‘Lichfield Friary’ on it.

Whatever the floor was, it was really big. We had found LOADS of tiles that looked the same, and maybe they belonged to the same floor. I started trying to see if any of the tiles might fit together, there were loads of circular tiles, some with patterns on, and some without. There was one round tile, with a triangle and circles intertwined in a pattern. There were also pizza shaped tiles, without a tip, like someone had taken a pizza and cut the middle out with a cookie cutter, if you get what I mean. Those tiles had a kind of moon, with a starfish shape in the middle.

We had found one of these tiles that was complete and one that was broken, but fitted back together again. All the rest were broken, but I managed to get a full circle out of the fragments we had found. It was like a massive jigsaw-puzzle, but I did it in the end, and what was even more exciting, was that the circular tile fit perfectly inside the ring of pizza shaped tiles! Same with the tiles with no pattern on, but we didn’t find another circular tile.

There was also another set of tiles. We had found about 8-10 of the same type, they were square, and they all had the same pattern on, the kind that can make 2 different types of patterns, depending on which way you put them.

Most of them were complete, apart from 3-4 of them which we only had corners of. I put them together, and they nearly made a 9 square pattern. These were my favourite tiles, and I hoped we found some more of them, we only had half a box or so left to get out. We did find a couple more of these tiles eventually. We finished emptying out the box, and then we started taking pictures of all the tiles. There wasn’t much time left, so we took all of the photos really quickly. As a result, not many of the pictures were very good. And the light was quite dim in the cells, so the light wasn’t the best either.

It was nearing the end of the session, so we had to put all of the tiles back in the boxes. I couldn’t help thinking that the tiles were from the old medieval Friary. At least some of them.

Kate asked me if I could do some research to see if the tiles were from the Friary, Me and my Mom went to the Lichfield Records Office, to go and look at ‘The Lichfield Friary’ by P. Laithwaite, which was reprinted from the Transactions of the Birmingham Archaeological Society where a report of Councillor T. Moseley’s findings from his exploration of the site in 1933 was given.

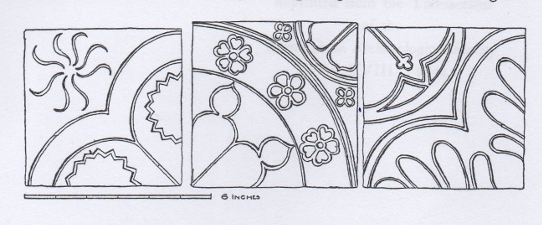

There were only 6 pages in the book. Page 5 had a drawing of some if the exact tiles we had found (the ones that looked like pizzas with the middle cut out) some with patterns, and some without.

Me and my mom were like O-O (AMAZED!). On the next page (page 6) there was a drawing on 3 tiles with different patterns on, all of which we had found in the box of tiles! 😀 (and my favourite one, the one that we had got like a 9 block square of the floor.)

D77/23/67 Drawing of square tiles from The Lichfield Friary by P.Laithwaite Copyright Lichfield Records Office

We had found what we had come looking for, proof that the tiles in the boxes were Medieval from The Grey Friars’ Church at The Friary!”

Note – this is not where the story ends! Lily is having an afternoon on the tiles with Jo Wilson, Lichfield City Council Museum and Heritage Officer and medieval tiles expert, Karen Slade this week, so look out for an update soon. Lily’s doing such a great job – the initial discovery, the ongoing research, and writing it all up afterwards – that I’m thinking of joining the Right Revd Jonathan Gledhill in retirement and leaving Lichfield Lore in her more than capable young hands.