As I mentioned in the last post about the West Gate, some other remnants of the Close’s medieval defences are visible. I’ve marked the ones I know about, on the map below, with a bit of information on each. I’m sure there’s probably more, and we could probably work out where the other defences were, but it’s a start!

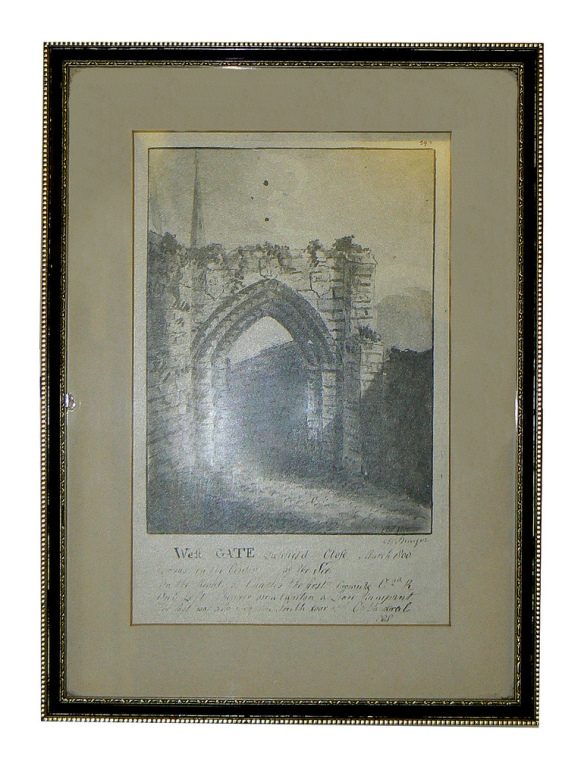

1. Site of the West Gate – see previous post here

2. Remains of North East Tower & ditch. A scheduled monument, sometimes known as the Bishop’s Tower, this was part of the original, medieval bishop’s palace. The pastscape record can be seen here. A description of the tower and how it fitted into the rest of the palace can be found in several books on the Cathedral & Close (1) and is based on a plan that was held in the Bodleian Library (is it still there?). A plan drawn from this can also be found here.

At the north east corner was a tower fifty two feet high and each of its ten sides thirteen feet on the outside. It was called the bishop’s tower and the ruins yet remain. Adjoining this tower was a square room with stone stairs leading to the top on the north west of which was an apartment with a cellar underneath twenty two feet in breadth and sixty three feet in length. The bishop’s lodging room was forty feet by thirty two with a leaden roof and cellar underneath. On the north side of this room was a large chimney piece opposite to which a door led to the dining room sixty feet long and thirty broad. At the east end was a door opening into the second tower which consisted of five squares eleven feet in width and thirty two in height. There were two apartments each twenty feet by seven separated from each other by the large hall chimney, , the lady’s chamber…the brewhouse…and the kitchen.

3. St Mary’s House. Incorporates a turret and part of the Close wall on the east and south side. Not only are there are arrow slits, but there are also rumours of a secret tunnel down below….Actually, it’s not that secret as loads of people seem to have heard about it.

4. Remains of Eastern Tower of South East Gate. This description comes from the ‘Lichfield: The cathedral close’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield

The gate built by Langton at the south-east corner of the Close had two towers. The eastern one, whose base was excavated in the late 1980s, was a half-octagon with 12-ft. sides. The western tower was presumably of similar dimension. The gate had a portcullis in 1376. There was a drawbridge, still in existence in the earlier 18th century, which crossed the outflow of water from Minster Pool, and also a wicket for pedestrians. The gate was removed in the mid 18th century in order to improve access for coaches into the Close.

There’s also this bit of wall behind the Chapters coffee shop, which provoked a bit of discussion on Brownhills Bob’s Brownhills Blog, and with Annette Rubery. Especially about what that recess is!

While I was having a flick through googlebooks trying to find information on the subject, I came across an interesting snippet. Adrian Pettifer, in ‘English Castles: A County Guide’ makes the point that that unlike the majority of cathedral cities, there was no wall around the city of Lichfield as a whole.

So whilst the Close was protected by a strong wall, a ditch, 50ft towers, drawbridges and portcullises (when you put it like that it really does sound like a castle!), what did the rest of the city have? Well, there was a ditch. It’s thought even this was used more for controlling traders coming in and out of the city, than for defences. An archaeological dig carried out on the Lichfield District Council carpark in Frog Lane, also confirmed that the ditch was used as the city dump and found a variety of material, including it appears, the dog from Funnybones. There were gates too, the positions of which are still marked by plaques. Again, though it’s thought these might not have been defensive. I think the ditch and the gates deserve a post of their own, so I’ll come back to them another time.

Credit: Ell Brown (taken from flickr photostream)

This will also give me time to think about my latest question (one I’m sure has been thought about and answered by clever people already!). Was the city of Lichfield defended, along with the Close? And if not, then why not? Of course, if anyone has any ideas about this in the meantime, please let me know!

Footnootes:

(1) This particular description is taken from ‘A short account of the city and close of Lichfield by Thomas George Lomax, John Chappel Woodhouse, William Newling

(2) Thanks to this website http://gatehouse-gazetteer.info/English%20sites/3329.html for pointing me in the direction of some great links.

(3) I’ve also used this book From: ‘Lichfield: The cathedral close’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990)