It’s the first day of Autumn today, meaning yesterday was the last day of Summer and it definitely went out with a bang. The storm seems to have subsided a little but the pounding rain continues its bleak fall and so I’m virtually visiting Streethay this afternoon. The village sits on the Roman Ryknild Street, just beyond the boundary of Lichfield City and, most appropriately given the weather, it’s a place with some watery links that I want to explore.

The new housing estates springing up around the outskirts of Lichfield are certainly controversial but one positive development at Streethay, is the arrival of Bod. I’m a big fan of the Titanic brewery bar and I do wonder whether this new influx of people would have kept Streethay’s previous pub ‘The Anchor’ afloat, if it had happened sooner. It was not to be however, and it closed in January 2015.

The building still survives and is now occupied by an Osteopathy Clinic and apartments but let’s go back in time to those days when it still served as an inn. It was clearly in existence by November 1848 when an inquest was held there on the body of Henry Crutchley, a fourteen year old lad who died after climbing onto an engine and slipping beneath the wheels of the wagons it was pulling, but was rebuilt around 1906, when the Lichfield Brewery Company was granted permission on the basis that ‘the house was in a most dilapidated condition and it was impossible to repair it’. I’ve yet to find a photo of its former form but I have found a reference in 1779 to a public house ‘known by the sign of the Queen’s Head’ which stood on the turnpike from Lichfield to Burton at Streethay and I’m wondering if this might be an earlier name. There are also mentions of a inn known as The Dog, around the same time and I’d like to sniff out where exactly that was.

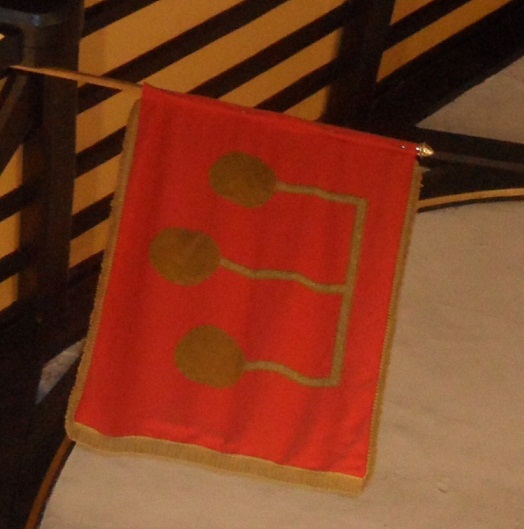

Photo © David Rogers (cc-by-sa/2.0)

In the Lichfield Mercury in 1972 an advert for the Anchor appeared with a curious reference to the ‘Klondyke Bar’, inviting you to enjoy your drink, ‘in the pleasant atmosphere of the Gold Rush’. One of the new apartments built in the grounds of the Anchor has been named after this, with the estate agents’ details explaining it was named after the ‘large wooden drinking hut’. Now I was given many nicknames by my brother when we were growing up, and one of them was ‘Klondyke Kate’. Whilst I’d like to think it was based on American vaudeville actress who provided inspiration for Scrooge McDuck’s girlfriend, I suspect it was more likely a reference to the British female wrestler. The Anchor’s Klondyke however is clearly a reference to the gold in them thar Canadian hills in the 1890s and was decorated with old photos and posters and, erm, pheasants, in a bid to recreate a prospectors’ bar. Much more of a mystery is why a bar on the outskirts of Lichfield chose it as a theme. In May 1979, the new licensees Norma and George Wolley presumably asked themselves the same question and relaunched the annexe bar as ‘The Mainbrace’. The hut itself had originally been a first world war army hut and this brings us nicely to a really interesting period in the pub’s history.

During the Second World War, the pub was frequented by personnel from RAF Lichfield. Jean Smith, in an interview with Adam Purcell, described how she and fellow WAAFs would stop off for a half a pint there on the way back home to their quarters on the opposite side of the road. On winter nights, when it was announced that flights had been cancelled due to fog and rain, the women would get their gladrags on and head out to the inn. Soon, the sound of bikes being propped against the wall of the pub would be heard as the lads from the aerodrome arrived at The Anchor, and the grounded pilots would soon be filling the air with cigarette smoke and tunes from the piano. The full interview with Jean can be found here and it’s a fascinating read, which really captures what the atmosphere was like for those young people living their lives in Lichfield, surrounded by the ever present threat of death.

This post was actually intended to be a deep dive into the village as a whole but I’ve got a bit overboard with the history of the Anchor Pub and so we’ll have to return to Streethay and its moated manor and plunge pool, the brewery and the canal wharf, and the lost hamlet of Morughale another day because we’ve only just dipped our toe in…

Sources

Birmingham Journal 25th November 1848

Lichfield Mercury 16th March 1906

https://www.onthemarket.com/details/8779282/

Lichfield Mercury 25th May 1979

Lichfield Mercury 7th April 1972

Adam Purcell, “Interview with Jean Smith,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed September 22, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/3488.

http://raf-lichfield.co.uk/Anchor%20Pub.htm

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol14/pp273-282