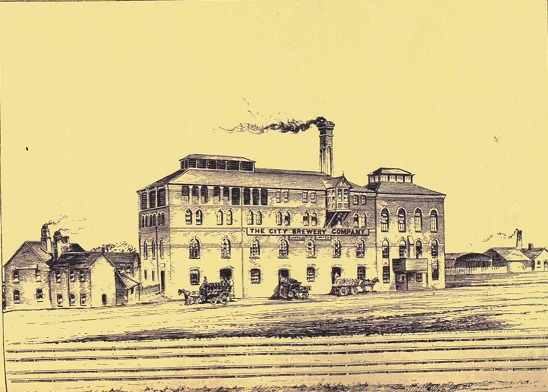

Before moving on to the Trent Valley Brewery, I’ve found a little more information to share on the City Brewery, regarding what happened on the night of the fire, and in the aftermath.

The Maltings survived the fire that destroyed the majority of the City Brewery in 1916.

At a Lichfield City Council meeting in November 1916, two versions of events were heard by those present. The report by Mr Salford, Captain of the City Fire Brigade, had already been accepted by the General Purposes Committee who told the meeting that they were satisfied with the work and conduct of the brigade, and proposed that the report, which I’ve summarised below, be adopted.

At quarter past five on the morning of 25th October 1916, the police telephoned him to say that the City Brewery was on fire. On hearing the news he turned out and met Fireman Gilbert in Lombard St, who was on his way to tell the Captain and the horsemen that they were needed. His own alarm bell had not rung, as it was out of order. On arriving at the Fire Station, some of the crew had already left with the hose cart and so, with the help of two others, he attached horses to the engine. On arriving at the Birmingham Rd, it seemed to the fire had been burning for some time. The engine was set up to work from the City Brewery basin of the canal with two lines of hoses, one of which was used inside the malt house (half of which was saved), and the other used to protect the boiler room (also saved). At some point, other crews arrived and though they battled hard against the fire in other parts of the brewery, it was beyond saving. The Captain believed that even if the other brigades had arrived at the same time as the City Brigade, the outcome would still have been the same, as the fire had already taken too much of a hold. A third line was set up at a hydrant in the brewery yard, but as the pressure was poor it was useless when trying to tackle the blaze in the high buildings and so was used on the wooden buildings between the brewery and the railway line, which were damaged but saved.

The other brigades in attendance left in the afternoon, with the Lichfield City Brigade returning to the Fire Station at 6.30pm. The Captain then returned at 8 o’clock to check the premises and was satisfied that it was safe. However, early the next morning, he received a call to say that something was burning at the brewery. This turned out to be one of the vats on the top floor and again, the poor pressure from the hydrant hindered the operation. However,the Captain didn’t believe it worthwhile getting the steamer out and left them (the brewery employees?) the standpipe and hose.

The main fire was thought to have started in the grinding room. Only one man was on duty and the Captain considered this insufficient cover. He also felt that there should have been a means for them to telephone for help immediately, without having to call for others to telephone and lose valuable time.

Other members of the Council weren’t so quick to accept the report and questioned the delay in responding, the lack of water pressure, and the out of order fire bell. The most critical of those present at the meeting, perhaps unsurprisingly, was Alderman Thomas Andrews, the City Brewery’s Managing Director. Despite initially claiming that he didn’t want to say too much, as he felt too strongly, the account he gave of the fire called into question the effectiveness of the Brigade (at one point Mr Andrews went as far as to call them ‘absolutely useless’). To summarise Mr Andrews’ version of events:

On discovering the fire, the man at the brewery told the cashier to call the police. An initial call was made at 4.45 am but due to difficulties getting through, a second call had to be made at 5.15 am. Mr Andrews admitted that as he had not been notified of the fire until just before 6 o’clock, much of his version of events was based on what he’d heard from others, but believed that it could be substantiated. He’d been told that the brigade arrived around quarter to or ten to six and then there were delays in getting to work as the hose burst two or three times. It had also been reported to him that at this time there was ‘absolutely no discipline or method’ amongst the fire brigade. Mr Andrews believed that if the Captain had followed his advice and sent his men into the brewery building to fight the advancing fire (something the Captain had refused to allow), then it would have been saved. He rejected the Captain’s claims that the brigade had saved the malt house, suggesting that that the hoses had only been turned onto this building at his and another brewery employee’s suggestion. Had it not been for this and the fact that the head maltster had gone inside to fight the advancing flames (with a rope around his waist in case he was overcome by fumes), then in his opinion, the malt house would also have been lost.

The Deputy Mayor acknowledged that Mr Andrews’ statements called for very serious consideration, but gave the brigade credit for doing everything within the means at their disposal, event though their means were absolutely inadequate! He considered half an hour to turn out reasonable, in view of the fact they were an amateur brigade but believed that the telephone call issues had lead to an unfortunate loss of time. Another of those present, Lord Charnwood, was concerned in relation to the telephone service, and the fact that there had been a serious allegation as to a mistake of judgement by the Captain (although believed that no doubt he had done his best). He suggested that a small sub-committee should be set up to examine the facts in more detail. Some of those present suggested there should be an independent enquiry, and other expressed concern that any members of the General Purposes Committee taking part in the enquiry may be biased towards their brigade’s captain. Eventually it was decided that the committee be made up of councillors, with the findings of the report presented to the whole Council (at a later date, an independent enquiry was deemed more appropriate after all).

I have found a report from the Annual Meeting of the shareholders of the City Brewery held in December 1916. The Chair, Mr H J C Winterton, stated that, due to the difficulties in rebuilding at the present time, it was difficult to know what the future had in store. The Ministry of Munitions had expressed their desire to protect and repair the partially destroyed buildings and he hoped that if manufacturing was able to resume at an early enough date, the company’s losses would be very slight.

We of course know that what the future had in store. The City Brewery was never rebuilt and what remained was sold to Wolverhampton and Dudley Breweries in 1917. The maltings remained operational until 2005, and is in the process of being converted to apartments.

I haven’t yet been able to find anything on the outcome of the enquiry, so I am unsure as to whether or not the Captain of the City Fire Brigade was found to be negligent in his duties. However, surely true negligence and error of judgement would have been to send ill-equipped men into a burning building (even with the ‘precaution’ of a rope around the waist!). The brewery may have been lost that night, but thankfully, lives were not.