A while back I wrote about Mr J W Jackson, the ghost hunting city librarian who wrote a local history column for the Lichfield Mercury in the 1930s and 40s. Last night I found an article about ‘dear old Beacon Street’, written by Mr Jackson in November 1943, in response to a letter from one of his old school friends who emigrated to Canada in 1870, at the age of twelve. Of course, in describing the changes that have taken place in seventy years, Mr Jackson gives us a glimpse of Beacon St in both his past and his present, which is actually now our past. Before things get too wibbley wobbley timey wimey, let’s move on to a summary of the changes Mr Jackson noted in Beacon Street over the seventy years leading up to 1943.

Mr Jackson says the old pinfold still remained but was hardly, if ever, used for its original purpose – in the past it frequently containing horses, cattle or sheep caught straying on the road and penned by official pinner, Watty Bevin. Fifty yards away from the pinfold as you walked back towards the city there used to be an old iron pump where the children used to fill up the vinegar bottles they were taking home from Hagues in Beacon St, after enjoying a couple of sips. The Anchor Inn kept by Billy Godwin had been cleared away and the field between the Inn and Smith’s Brewery was now the residential school. The brewery itself where the children took cans to be filled with barm had been converted into a foundry.

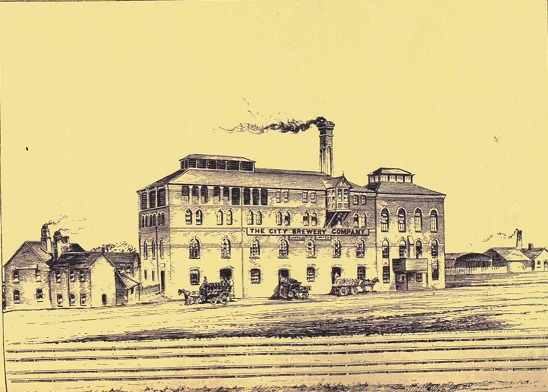

The Fountain Inn still remained but visitors from the Black Country no longer came to play bowls on its lawns. The Lemon Tree Inn, kept by Sam Boston was now a house, as was the old butchers shop (kept by Mr Yeomans) and the Pheasant Inn previously kept by Mr Stone is also a house. The wall shutting off Beacon Hall had been partly taken down and was now a garage and a residence. The old fashioned grocery shop at corner of Shaw Lane, owned by Mr Hall had been sold and replaced by a much larger shop, eventually becoming an antiques shop. Whitehall and Milley’s Hospital remained as they were in 1870 but the Free Library & Museum had been built near to the site of Griffith’s Brewery. (Note: Think this was probably earlier – Free Library & Museum built 1859?)

The Angel Croft was described by Mr Jackson as ‘now a hostel’. The Old Beehive Inn had also been converted into a residence as had the Wheel Inn at the corner of Wheel Lane. The windmill where Mr Jackson played as a child was no longer in use but converted to a picturesque residence. Apparently the miller came in a considerable fortune and disappeared leaving everything as it stood and nothing was heard of him again.

Council houses known as Beacon Gardens had been built on the fields in front of the Fountain Inn. The old blacksmiths, where legend has it that a French man once took his dancing bear to be shod was still going strong. The Feathers Inn was still licensed and the row of cottages adjoining was much the same. The Old St Chad’s Rectory garden and field had been built over, the new road known as Nether Beacon. By 1943, the wheelwrights shop on brow of Beacon Hill had long since disappeared but the Little George Inn still stood as did the George & Dragon.

Of course, we can also now compare Beacon St seventy years on from when Mr Jackson did his comparison. I took most of the photos on Sunday (before I found the article weirdly!). The old pinfold still remains, but I doubt anyone now even remembers it being used to lock up straying animals.

The residential school has now been converted into apartments and the site of the Foundry is now Morrison’s Supermarket. Funnily enough you can probably get barm, or something similar there once again, as I think it’s a type of yeast (as in the northern ‘Barm Cake’). The Fountain Inn is still open, and Milley’s Hospital and Whitehall are still there. The Free Library and Museum building is of course now used as the Registry Office. As we are all too aware the Angel Croft is still there, but for how much longer in its desperate state?

The blacksmiths has gone but is not altogether forgotten with road names ‘Forge Lane’ and ‘Smithy Lane’ to remind us. The Feathers Inn is still licensed but has now expanded into the row of cottages adjoining (for the record, I had a very nice jacket potato in the beer garden there on Bower Day this year). The George and Dragon, thankfully, still stands but the Little George is now a private, rather than public house. According to John Shaw’s Old Pubs of Lichfield, after WW2, the licence of the pub was transferred to the new pub on Wheel Lane, known as the Windmill. This ‘new’ pub which, wasn’t around in Mr Jackson’s time will probably not be around for much longer, as it is has been closed for some time and the site earmarked for development.

Mr Jackson’s article reminds me of the need for recording the everyday and the seemingly ordinary, as one day the present will be the past and what was once commonplace may no longer be. I’m a big believer in using place names that reflect the history of a place, but on its own, a street sign for ‘Smithy Lane’ only tells you part of the story. Had Mr Jackson not added the story of the dancing bear’s shoes and the missing miller and his money to his reminiscences, they may well have been forgotten. “So what?” some may say, dismissing them as mere trivialities, but I disagree. I think stories matter.

Perhaps in seventy years time someone will look back at how Beacon St was in 2013. I wonder what will have changed and if we’ll have left them with any good stories?

Sources:

Lichfield Mercury archive

The Old Pubs of Lichfield, John Shaw