Once, when Cuthbert Brown was a boy and the circus came to town (sorry, city), one of the elephants died and was buried on Levett’s Fields. Mr Lichwheeld and I had joked that we should organise a community archaeological dig to look for Nelly but with work starting on the demolition of Lichfield’s Fire Station recently, this may prove unnecessary.

In the pre-Friary Road days, the Big Top also used to pitch up at the Bowling Green fields. Presumably at that time the Bowling Green pub was still a seventeenth century timber framed building. The only image of this I can find online is included in the 1732 engraving of the south west prospect of the city, as seen here on Staffordshire Past Track (zoom in and it’s the building in the foreground, beneath the central spire of the cathedral). The pub was rebuilt in the 1930s but the Victoria County History mentions that a clubhouse still in existence in the 1980s may be the same one which existed in 1796. Definitely worth a trip to the pub.

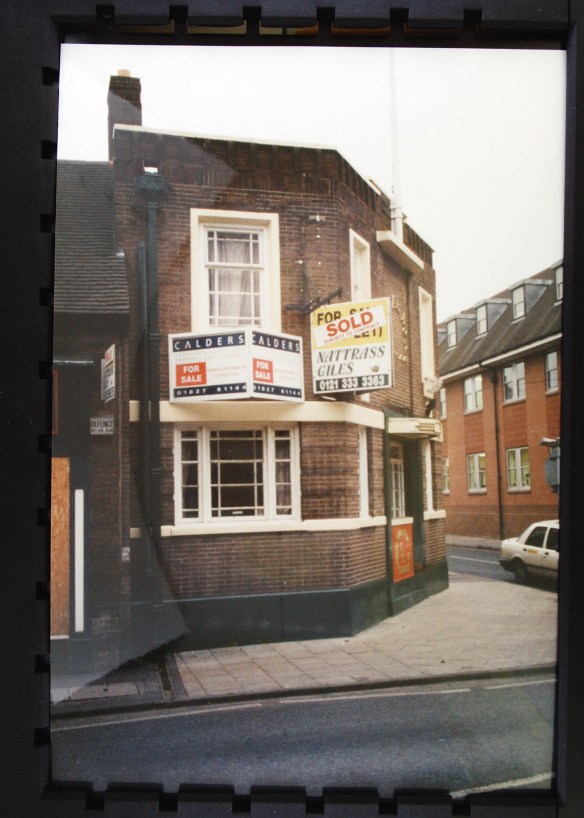

The Friary prior to development. Taken from Gareth Thomas’ (GIS Officer for Lichfield District Council) Pinterest site

One of the best things about looking through old newspapers is that you come across stories that you wouldn’t even think to look for. Whilst searching for more information on the Bowling Green, I came across the following obituary from March 1820.

At Lichfield, aged 67, John Edwards, the Hermit of the Bowling Green in that city. He came to the neighbourhood in the prime of life – a perfect stranger, retiring with disgust or disappointment from other and brighter scenes of life; but further particulars have never transpired respecting his history. The subscriptions of the benevolent have contributed to shed a comparative comfort on his latter days. A short time previous to his decease, he published a short “Essay on Freemasonry”. The medical gentlemen gratuitously attended his during his illness.

So many questions about Mr Edwards arise from this small snippet but I suppose if further particulars respecting his history had not transpired back then, the chance of uncovering anything now is fairly slim. Is it fair to say that Mr Edwards’ attempts to distance himself from society seem to have inadvertently made him into a celebrity of sorts? I wonder what became of his Essay on Freemasonry?

Whatever Mr Edwards’s reasons for preferring a life a solitude, it seems that in the eighteenth century it could be a career choice. Of sorts. Apparently, always on the lookout for opportunities to impress or outdo their friends and neighbours,eighteenth century land owners employed professional hermits to sit and be mystical amidst their fake temples and other follies. I found an example in the form of Mr Powys of Morcham (Morecambe?) near Preston, Lancashire, who advertised an annuity of £50 per annum for life to,

…any man who would undertake to live seven years underground, without seeing anything human, and to let his let his toe and finger nails grow, with his hair and beard, during the whole time.

Board and lodging was provided in the form of apartments said to be, ‘very commodious with a cold bath, a chamber organ, as many books as the occupier pleased, and provisions served from his (Mr Powys’) own table’. By 1797, it was reported that the ‘hermit’, a labouring man, was in his fourth year of residence, and that his large family were being maintained by Mr Powys. Just what quality of life must a man with a family have been leaving behind to agree to live like this? If this was about showing off to others, it’s curious that Powys stipulated that his ‘hermit’ was to live without seeing anything human.

In August 2002, around two hundred years after this dark appointment, notices appeared in The Guardian, The Stage, The London Review of Books and the Staffordshire Newsletter, advertising for an ‘ornamental hermit’ to take up residence at the Great Haywood Cliffs near the Shugborough estate in Staffordshire, as part of an exhibition called ‘Solitude’. The Shugborough Hermit would be required to live in a tent near to the cliffs (living inside them was deemed too risky) and only had to commit to the weekend of the 21st and 22nd September 2002. Out of two hundred and fifty enquiries from all over the world, artist Ansuman Biswas was chosen and I’d love to hear from anyone who visited him at Shugborough that weekend. Mr Biswas went on to spend forty days and forty nights alone in the Gothic Tower at Manchester Museum in 2009, with the aim of becoming, ‘symbolically dead, renouncing his own liberty and cutting himself off from all physical contact”‘.

I think I’d rather run away and join the circus.

Sources:

The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome, Gordon Campbell, Oxford University Press 2013

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/2205188.stm