At the church of St Michael’s and All Angels, in Hamstall Ridware I was greeted by four arms waving (a sword) at me from a tomb. It belongs to the splendidly named Thomas Stronginthearm, who left this small village for the bright candles of Chicago in 1803, before making a final journey back home home to rest in the Staffordshire soil which his family had toiled upon – according to the church booklet, the Stronginthearms were yeoman famers.

The name appears several times in the Hamstall Ridware parish registers, available online here, recording all those who were baptised, married and buried here between 1598 and 1812. There are also other snippets of information on life in the village, including an entry in June 1806 when the Rector Edward Cooper led twenty five parishioners on a procession around its boundaries, beginning at Gallows Green, going along the Yoxall Rd as far as Sutton’s Farm, and then proceeding towards the Trent. Later that Summer, Edward’s cousin Jane Austen came to stay with him for five weeks, and it’s believed that she may have used Hamstall Ridware as inspiration for the fictional ‘Delaford’ in Sense and Sensibility. http://www2.lichfielddc.gov.uk/hamstallridware/about/

On the subject of baptism, there are three fonts here. Inside the church is the one that is currently used, which dates from nineteenth century and there’s the lovely Norman bowl which was relocated here from the church of St James at Pipe Ridware. Outside, and being used as a flowerpot, is the third, also said to be Norman. At the time of the Burton Scientific Society’s visit to the church in 1924, this font was on the vicarage lawn. One of the society members, a Mr Noble claimed that it was the relatively recent work of an Armitage mason who did a good trade in producing mock ancient stonework, for people with antiquarian tastes. However, the Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland seem happy that the font is twelfth century, and presumably they know what they are talking about.

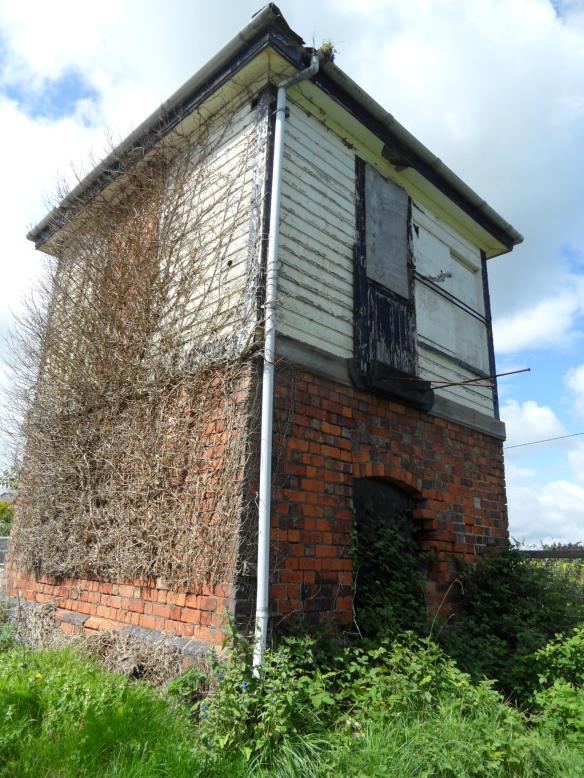

There’s also the base of a medieval churchyard cross here to which a much later shaft and cross have been added, although a fragment of the original shaft remains nearby. It was while I was having a look at this, that I noticed the ruins of a brick building, looming up behind the church tower. This is the late 15thc/early 16thc watch tower, once part of the now derelict manor house, Hamstall Hall. When the Burton Scientific society visited, they climbed a wooden staircase to the roof where they enjoyed ‘a good view of the surrounding area’ – it’s said that you can see four counties from the top. Given that that the hall features on the ‘Heritage at Risk’ List and is considered to be at risk of collapsing, it’s probably best to take their word for it. There are other remains of the hall here too, which I missed, including a Tudor gateway, and the porch to the old hall.

Showing St Michaels Church and the tower of Hamstall Hall in the background.

© Copyright Graham Taylor and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

In June 1939, the Derbyshire Times did a feature on a ninety three year old woman known as ‘Grannie Shelton’, who worked as a parlour maid and nurse at the hall, and married her husband on 19th March 1863 at St Michael’s. She told the paper that she had never seen a ghost but had once, ‘been down amongst the dead men’ – when a member of the Squire of Hamstall Hall’s family died she entered the family vault to have a look around and saw six coffins inside, each covered by a black cloth but with the white face of each of the corpses visible through the glass. Mrs Shelton also once dressed up as a ghost to scare the pantry boy that she suspected of stealing fruit from the Hall, causing him to run for his life shouting ‘The Devil is in the pantry!’ The devil may not have been in the pantry, but apparently he was found in a small hollow compartment in one of the bedrooms of the old manor house in the form of a stone image, complete with horns, depicted as ‘shaving a pig with red skin’ (I swear that I haven’ t made this up!). The report suggests that the Hall was formerly a Nunnery, and this hollow would have been somewhere nuns would carry out penance for breaking the rules. I can’t see any reference anywhere else to hall being used as a convent and I can’t help but wonder if it could have been a priests’ hole? The hall belonged to the Catholic Fitzherbert family from 1517 to 1601. Sir Thomas Fitzherbert was imprisoned in the Tower of London for thirty years until his death on 2nd October 1591. All pure speculation on my part.

Feel like I’ve only just dipped my toe into the (holy) water when it comes to the history of Hamstall Ridware…