Many people are familiar with the story of John Neve, William Weightman and James Jackson, the last men to be hanged in Lichfield on 1 June 1810, for the crime of forgery. Their shared headstone can be seen tucked away under the tower at St Michael’s, although they are buried elsewhere in the churchyard in a now unmarked a communal grave. One particularly poignant postscript to these events is that after his execution, the friends of John Neve commissioned three mourning rings to be made, each with an inscription to his memory and containing a lock of his hair. I wonder whether it was these same friends who erected a headstone as to my knowledge there are no memorials to any of the other executed criminals buried here?

Amongst them is another tragic trio, Thomas Nailor, Ralph Greenfield and William Chetland who met the same end for the same crime at the same place on 13th April 1801. Prior to their execution, two of the men had attempted to escape from Lichfield gaol by filing through their irons and putting them back together with shoe maker’s wax. Their cunning plan had been to knock down the gaoler when he came to lock them up for the night and they would have gotten away with it had it not been for pesky Joseph Vaughton, a private in the 38th regiment of foot, to whom Nailor had given a pattern of the wrench he wanted making and a Bailiff called Mr Scott who discovered the file they had been using. Headstone they may not have but incredibly a tangible link to this execution does apparently exist. In 1947, the Town Clerk of Lichfield received a letter from a Mr Clayton W McCall of Canada to say a morbid memento had turned up in an antique shop in Vancouver in the form of a silver salver, ‘Presented by the Corporation of the City of Lichfield to Revd. Bapt. Jno. Proby, Vicar of St Mary’s, for his pious attention to three unhappy convicts who were executed in that City April 13th 1801’. However, as with the rings, its current location is unknown.

One very unhappy convict sentenced to be hanged at the gallows on 6th September 1782 was 62 year old William Davis who had been convicted of horse theft. The Derby Mercury, reported that in his final moments, David’s behaviour was bold, paying little attention to anything that was said to him. Then, just as the executioner was about to send him eternity, Davis threw himself from the cart with such force, that the rope snapped. After much confusion and delay, the rope was replaced and Davis’s last earthly words are recorded as having been, ‘This is murder indeed!’.

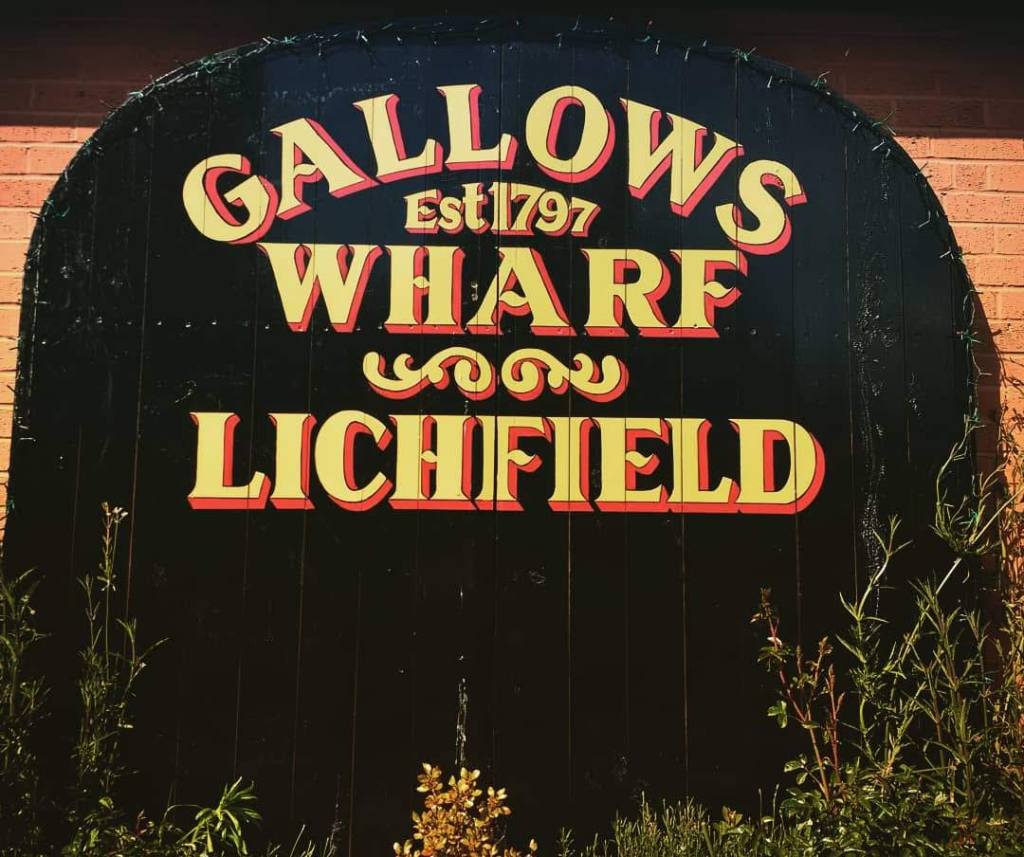

In 1935, the site of the old gallows was described as being ‘preserved and indicated to passers-by with an inscription recording its ghastly use in bygone days’. The area has developed significantly since then, but I was told by Janice Greaves, former Mayor and current Sheriff of Lichfield, that the exact spot where the gallows stood is now marked by a walnut tree growing on the patch of grass alongside the garage. There has been some discussion about what form the gallows actually took, but there is evidence to suggest that there was a permanent structure to which the cart carrying the condemned convicts would be brought. In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette it describes how ‘On Friday Night last, Richard Dyott Esq, who lives near Lichfield was going home from thence, he was stopp’d near the Gallows by two Footpads, who robb’d him of five Guineas, and in the Scuffle he lost his hat’.

My plea to you this Halloween is to keep your eyes on Ebay for Neve’s mourning rings and the silver salver. If however you decide to take a wander over to Gallows Wharf in search of Richard Dyott’s hat, please be warned that an ex-executioner from centuries past appears to have been sentenced to linger at the spot and you may well feel a push from behind as he attempts to dispatch you to your doom.

Sources

Evening Dispatch 31st March 1935

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 3rd February 1752