Hopefully, anyone reading the blog recently has found the old graffiti interesting. I know that Gareth and I, and (for a few days at least!) a large broadcasting corporation did. After all of the excitement, I thought it was time for a bit of musing….

The discoveries (or perhaps rediscoveries is more accurate) in the Lichfield District Council offices got me thinking about the potential for other ‘unseen’ history out there. There’s unseen in the sense of being hidden away from view – in attics, down pub cellars and down the bottom of the garden. However, I also think that something in plain view can be unseen – people may pass by everyday, but no longer see what’s actually there or the potential of it, due to familiarity. During discussions about the graffiti, someone said to me, “I’ve walked past that graffiti loads of times and never even thought about it”.

The bread oven above is in the house of someone I know. I remember them buying the property years ago and excitedly telling me after their first viewing with the estate agent, “It has an old bread oven!”. When they moved in we all keen to peer inside but prior to taking the photo, it was last interacted with as part of an Easter Egg hunt. However, taking the photo to show a friend, sparked a whole new conversation about the oven. Was it original? If so, would this have been the kitchen? Wasn’t it once divided into two houses? How was it laid out back then? Why was the house built in the first place? And so on….My point is, sometimes, we need to look with a fresh pair of eyes to see what’s in front of our nose.

I don’t think that the history in question even has to be a specific feature like the bread oven. I find the traces of people’s everyday lives fascinating. I visited a house in The Close last Christmas. Unfortunately, I hadn’t had nearly enough mulled wine to pluck up the courage to ask if I could take photos, so I’ll have to describe it. There were stone steps down into the cellar, worn away in the centre by centuries worth of footsteps. There were attic beams with layers of fading wallpaper still clinging to them up in the attic. To describe the place as ‘lived in’ would be an understatement. The next question inevitably is ‘lived in by who’? Actually, photos wouldn’t really have done the place justice anyway because it was more than a visual thing. You wanted to touch, as well as see. ….

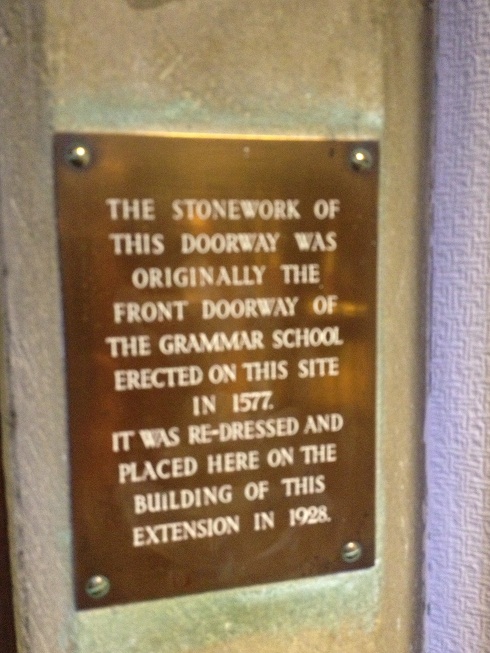

I’m really hoping that Lichfield District Council open their offices up for the next heritage weekend, so that people get to look around what was one the Old Grammar School for themselves. I’m not suggesting people throw the doors of their homes open to the public, but perhaps if we want to explore the history of the city and all its inhabitants, we sometimes need to look at the ‘normal’ buildings and places, where people lived and worked, and still do! I’m by no means detracting from those special, extraordinary buildings like the Cathedral, just saying that sometimes it might be worth looking again a little closer to home.

A selection of objects found in the garden Of Vicky Sutton’s Nan’s house near to Beacon Park (not including the pink flowery plate!).

Edit:

After I woke up properly, I realised this actually said R Crosskey. I found a book about Henry William Crosskey, a geologist and Unitarian minister from Lewes (1) and found that his younger brother, Rowland Crosskey came to Lichfield as an apprentice ironmonger. He emigrated to Australia for a while and then, after he returned to England, he started a business in Birmingham. Afterwards, he took over the Lichfield firm where he had served his apprenticeship. In 1868 he became Mayor of Lichfield and donated a civic sword to the City (Is this the one still used in processions today?). He died in 1890. From census records, it looks like his home and business premises were initially in Market St. In 1888, he was in Bore St, trading as a ‘Military Camp and Store Furnisher’ with premises on the Burton Rd in partnership with Charles John Corrie. Also, just as a point of interest, Rowland was his Mother’s maiden name.

(1)Henry William Crosskey, LL.D., F.C.S. : his life and work by Richard Agland Armstrong; with chapters by E. F. M. MacCarthy and Charles Lapworth. http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/e-f-m-maccarthy-richard-acland-armstrong.shtml

(2) London Gazette 1888