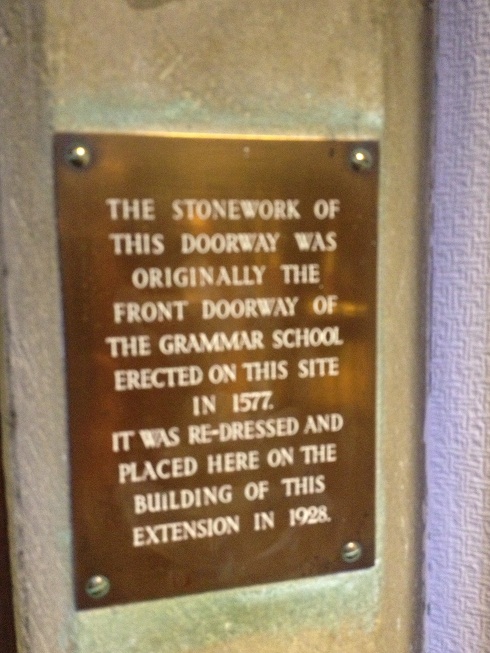

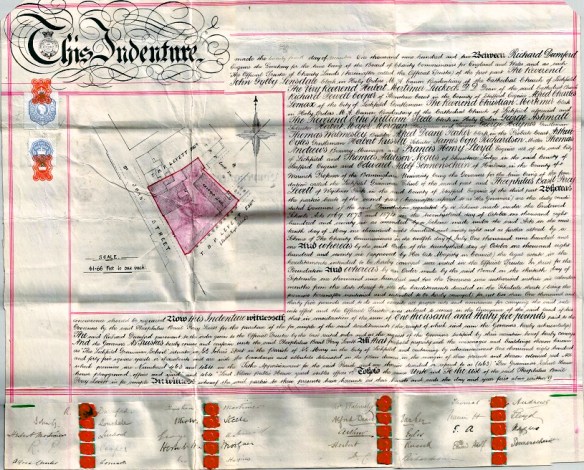

Following on from this morning’s post, here is Gareth’s latest fantastic Lichfield Grammar School related discovery. The plaque suggests that this stonework was originally the front doorway to the Grammar School, and was redressed and placed around this doorway in the Lichfield District Council Offices in 1928. The second photograph shows our oldest dated graffiti yet – RS 1681.

As I’ve been reading about the school’s history, I’ve been jotting down the names of students. Here they are so far, in no particular order….some you may recognise, others you may not.

Isaac Hawkins Browne Gregory King

John Wyatt George Smallridge

David Garrick Andrew Corbet

Thomas Newton John Willes

Robert James Thomas Parker

Elias Ashmole William Talbot

Edmund Hector William Noel

John Taylor Richard Lloyd

Charles Congreve Samuel Johnson

William Wollaston Theophilius Buckeridge Lowe

Francis Chetwynd Joseph Addison

John Rowley Henry Salt

John Colson Joseph Simpson

Walter Bagot Charles Bagot

William Bailye

Do any of them match any of the initials found throughout the school? I have to say it’s the ones we don’t know much about that interest me the most. We all know what Mr Ashmole did, but what about those whose achievements weren’t documented to the same extent? What about those poor boys (with or without their brooms)? How did attending the school affect the course of their lives?

Image taken from Wikimedia Commons. Murray, John. Johnsoniana, 1835. reprinted Lane, Margaret (1975), Samuel Johnson & his World, p. 26. New York: Harpers & Row Publishers

Several engravings and drawing of the Grammar School exist showing the schoolroom building at various stages in its history. Gareth is working on something that will hopefully show the changes in the schoolroom since it was first erected on the site in around 1577. This should hopefully help us to discover the original location of the stone doorway too. The schoolroom was rebuilt in c.1848, and as the dates on the stonework are before and after this date, I wonder whether materials from the old schoolroom of 1577 were reused in carrying out this restoration work? I’m hoping to go to the Lichfield Record Office as the National Archives catalogue is showing that the hold lots of information on this, and on may other aspects of the school’s history, dating back to around the same time RS carved his initials into the old doorway.

Finally (for now!), I’ve suggested that the doors of the Old Grammar School, both inside and out, be opened to the public for the Lichfield Heritage Weekend.

Update:

I found a book ‘The Wanderings of a Pen and Pencil’ from 1846, in which the authors FP Palmer and A Crowquill desribe their visit to Lichfield. Illustrations of the exterior and interior of the Grammar School are included in the book. Interestingly, their visit was at the time the school was in decline, and there were no pupils attending (see previous post). They record that the upper schoolroom was tenanted by lumber, and the lower school room unoccupied, and asked ‘How is it the Lichfield Grammar School is so shamefully deserted and what amount is received by the master for doing nothing?’. In the interior, the stool that they have sketched was apparently the ‘flogging-horse’. The exterior drawing confuses me further – hopefully Gareth will be able to shed more light on how this compares with the other views of the schoolroom we have!.