There’s some evidence that there were several stone crosses in Lichfield, although as far as I know, no physical remains have ever been found.

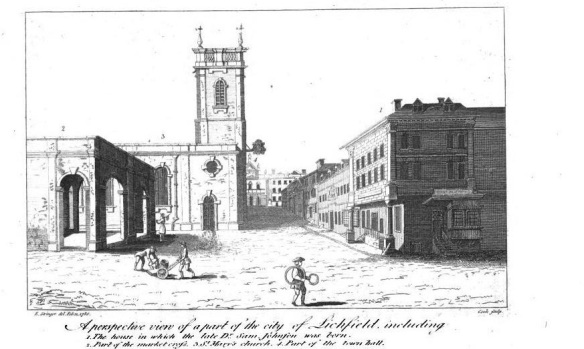

The most well documented of these is the market cross. According to the Lichfield volume of the History of the County of Stafford (1), a market cross stood north of St. Mary’s in the late Middle Ages and then some time around 1530, Dean Denton surrounded it with eight arches and added a roof to keep the market traders dry. The building was topped with eight statues of apostles, two brass crucifixes on the east and west sides, and a bell, as you can see in this picture on the Staffordshire Past Track site. The cross was destroyed in the civil war, and replaced with a market house, as shown in the illustration below (although it is referred to as a cross on the notes?) which has also now disappeared.

There is a possibility that there was a preaching cross in the grounds of St John’s Hospital as documentation shows that Dean FitzRalph preached outside in the cemetery. (2) Information on this specific example is really sketchy, but there is a surviving preaching cross in Bloxwich which you can read about in a great article on The Borough Blog.

More evidence exists for a cross at the junction of Tamworth St and Lombard St. There is a cross like structure shown there on John Speed’s 1610 map, and in 1805 Thomas Harwood wrote that there was a stone cross in Tamworth St. (3) There are also a couple of references in old property deeds such as one from April 1316 describing a ½ burgage in street between the Stone Cross and Stow Gate.(4)

The Market Cross and the Stone Cross at Tamworth St can be seen depicted on John Speed’s 1610 map of Lichfield

A cross apparently stood near Cross in Hand Lane in Lichfield, giving rise to a theory that it this is where the lane got its name from (the other theory is that is was a pilgrimage route, to St Chad’s shrine, where people would walk with ‘cross in hand’. The route has recently been incorporated into a new pilgrimage and heritage route called Two Saints Way). Harwood said, “(Beacon Street) extends from the causeway over the Minster pool which separates it from Bird Street to houses at the extremity of the city called the Cross in the Hand and where stood an ancient cross ad finem villas.’ The pastscape record for the cross is here.

This week I came across another reference, this time Bacone’s Cross, and which was also thought to be in Beacon St, at the end of the town. Was the ancient cross at Cross in Hand Lane and Bacone’s Cross the same cross?

The Bacone’s Cross/The Cross in Hand and the Tamworth St cross were both situated at the ends of the town. Does this mean that they were boundary markers of some sort? If so, could there have been more crosses marking other places on the City’s boundary. There were city gates at both Beacon St and Tamworth St. However, the probable sites of the gates don’t correspond exactly with the probable sites of the crosses e.g. the above example says ‘between the Stow Gate and the Stone Cross’.

Tamworth Gate plaque on Lee Garden Chinese Restaurant Credit: Ell Brown (taken from flickr photostream).

In the absence of more information about Lichfield specifically, I looked elsewhere to see if crosses would have been used to mark boundaries. St Albans was surrounded by a ditch, like Lichfield (and there’s a link with the story of the Christian martyrs but that’s a bit too much of a tangent for now!). The History of the County of Hertford, says this about the city’s boundary (5)

Crosses were at an early date erected at important points in the line of boundary, and at each of the entrances to the town, namely, the Stone Cross or North Gate Cross at the north on the Sandridge Road, the Red Cross in Sopwell Lane, at the entrance by the old road from London, the Cross with the Hand in Eywood Lane, the Black Cross, probably at the angle where Tonmans Dike goes from the boundary of the houses in Fishpool Street towards the Claypits, and St. John’s Cross at an angle of the boundary in what is now known as Harley Street, but lately as Mud Lane.

It’s interesting to see that some of the names are the same – Stone Cross, Cross with the Hand – but I don’t want to start jumping to conclusions until there is much more evidence!

Finally, there is a document relating to property in Freeford (4), which describes ‘three selions of land at Lichfield, near Le Hedeless Cross, on the road towards Freeford’ in the time of Edward III – Henry V. Does this refer to the Tamworth St Stone Cross, or another cross altogether?

What happened to these crosses? Time? Religious differences? Where did they end up? There’s something in one of my all time favourites book that gives me hope (possibly misguided) that there is a chance, no matter how slim, that things that have long been thought to have vanished might turn up again one day in some form or another. In England in Particular (6), in the section on Wayside and Boundary Crosses, it says that,

Some crosses have been found in hedgebanks, with shafts used as gateposts. A number have been found by researching field names:two fields called Cross Park revealed previously undiscovered stones.

Fingers crossed!

Edit:

In view of the above, I thought it’d be worth having a look at field names etc, in Lichfield. There is an entry in an transcribed inventory relating to the real estate of the vicars that says Deanslade: Falseway to cross called Fanecross (4). There’s a Banecross on another transcription and I think one of these could be down to a typo and that they could be the same place, There is also an entry for a place known as Croscroft, which was on the road to Elford, near St Michael’s Churchyard (3)

Another edit:

I was hoping there would be an ancient cross somewhere in Lichfield. Well, I finally found one! Actually that’s a fib. What I found is a photograph in a book of archaeologists finding one. A decorated cross shaft was discovered built into the foundations of the north wall of the nave of Lichfield Cathedral. It’s thought to be Saxon or Saxo-Norman, and could be a surviving remnant of the earlier church on the site. I wish I could share a photograph here, but all I can do is tell you that it’s on plate 1 in the ‘South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions 1980-1981 Volume XXII’ book, on the local history shelves at the library!.

Sources:

(1) Lichfield: Economic history’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield(1990), pp. 109-131http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42349#s6

(2) Hospitals: Lichfield, St John the Baptist’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 3(1970), pp. 279-289

(3) The history and antiquities of the church and city of Lichfield by Thomas Harwood

(4) Collections for a History of Staffordshire Part II- Vol VI (1886), William Salt Archaeological Society

(5) ‘The city of St Albans: Introduction’, A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2 (1908), pp. 469-477

(6) England in Particular, Sue Clifford & Angela King for Common Ground