The plan was to spend the day foraging for folklore in the villages to the west of Stafford but we accidentally ended up at Acton Trussell and then found out that archaeologists had accidentally found a Roman villa underneath the local church.

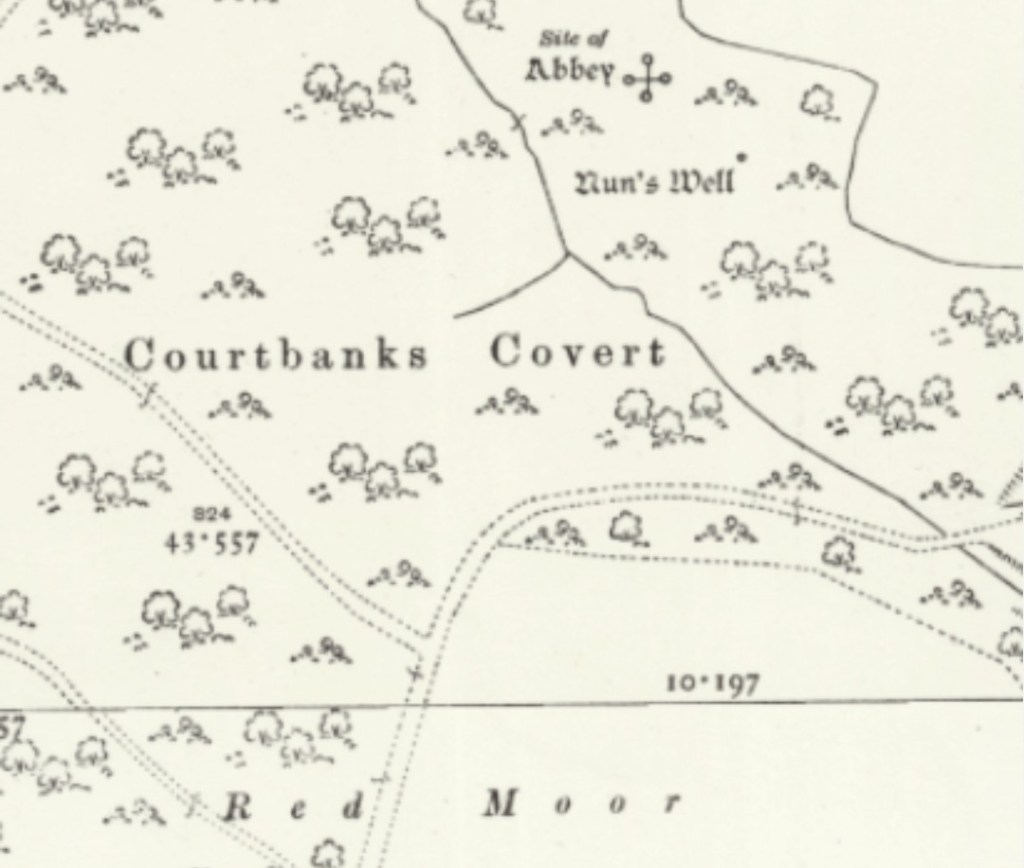

In the 1970s, a local archaeology group started to wonder why the church of St James was built someway outside the village. Clearly the two women we asked for directions to the church who after asking, ‘What church?’ then sent us in entirely the wrong direction, thought it should have been nearer to the village too. The obvious assumption was that the centre of Acton Trussell has shifted over the years but when fieldwalking between the church and village produced just a scattering of late medieval pottery, this seemed unlikely. What did start showing up however was evidence that there had been Roman activity at the site. Several sherds of pottery and two coins from the 3rd century posed a new question. What were the Romans doing here?

To the south of the St James, the field-walkers found fragments of roof tiles, suggesting the source of the Roman remains was somewhere near the churchyard. and then an excavation which began in May 1984 revealed that the church of St James and its graveyard actually stood upon the site of a Romano-British villa. Was this just a coincidence or could there be some sort of deliberate continuity here?

Late 2nd C. Apsidal wing of Roman Villa, taken Friday, 5 July, 1985

It’s not unknown for Roman sites to have been converted to Christianity. I was at Wroxeter in the summer and read that part of the Roman complex at Viriconium may have been adapted for use as an early church. It’s not watertight but the availability of a cold plunge pool in the frigadarium and bodies found nearby hint that the baths may have been used for those two Christian bookends of baptism and burial.

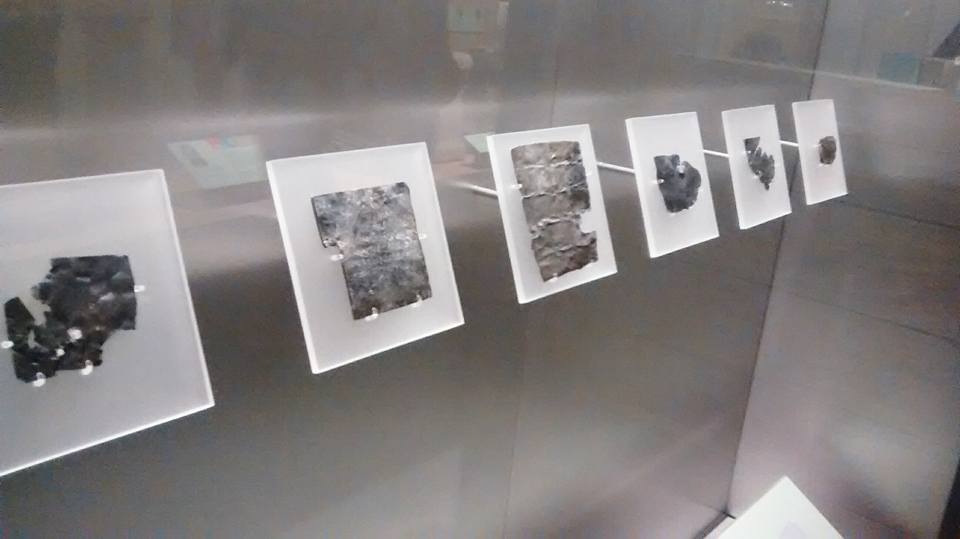

This brings me back down the A5, and makes me wonder about Wall, where there are clues that Letocetum may have been home to an early Christian community. Again, evidence is mostly circumstantial but the most convincing argument comes in the form of a long lost bronze bowl with a Chi-Ro symbol on it. It was discovered in a grave in 1922 along with 30 coins dating to the 4th century and one of the 1st century and exhibited by Mr F Jackson at Wroxeter at a meeting of the Birmingham Archaeological Society. Afterwards it disappeared. and is now probably in a private collection but it belongs in a museum (yes, I have been watching Indiana Jones over the Christmas holiday). Thankfully, the other physical evidence that Christians once worshipped at Wall is in a museum. Well, in the Birmingham Museum Collection Centre anyway. Amidst stones carved with heads and horns, believed to have come from a Romano-British shrine local to Letocetum and rebuilt into the walls at Wall, was a stone carved with a cross.

Archaeologist Jim Gould suggests stylistically the cross most likely belongs to the period of the 6th to 9th century, which would tie it into the time-frame of the tantalising verse that is, ‘The Death Song of Cynddylan’ which recalls three battles fought by Prince Cynddylan of Powys. One of these was at a place called ‘Caer Luitcoed’, which translates to ‘the fortified grey wood’ or, as everyone now calls, Lichfield. Here’s a translation of the relevant part of the poem:

Before Lichfield they caused gore beneath the ravens and fierce attack

Lime-white shields were shattered before the sons of Cynddylan.

I shall lament until I would be in the land of my resting place for the slaying of Cynddylan, famed among chieftains.

Grandeur in battle, extensive spoils

Moriel bore off before Lichfield

1500 cattle from the front of battle,

80 stallions and equal harness.

The chief bishop wretched in his four-cornered house

The book clutching monks did not protect

those who fell in the battle before the splendid warrior.

The relevance to a possible early Christian community in the area are those book-grasping monks and the bishop in his four cornered house. According to Jim Gould, written evidence can also be found in Eddius Stephanus’ Life of Bishop Wilfrid which suggests that there was some sort of church and monastery in the area before St Chad set up alongside the spring at Stowe. Wulfhere, King of Mercia between 657 and 674, gave lands to Bishop Wilfred to found monasteries at existing holy places deserted by British Christians.

It wouldn’t be a complete leap of faith to imagine this could have included Lichfield, would it?

https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/photos/item/AO56/208/8

https://actontrussellromanvilla.weebly.com/

https://www.wallromansitefriendsofletocetum.co.uk/index.asp?pageid=709225

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/2415.64

The Archaeology of Roman Letocetum (Wall, Staffordshire), Implications of the proposed West Midlands Northern Relief Road, Draft for Consultation, County Planning and Development Department Staffordshire County Council

Gould, J 1993. ‘Lichfield before St Chad’, in Medieval Archaeology and Architecture at

Lichfield (ed J Maddison), Brit Archaeol Assoc Conference Trans 13, 1–10, Leeds: Maney Publishing