The run up to Halloween feels like the right time to resurrect the blog and, in keeping with the spirit of my favourite season, it’s my intention to share some of the more sinister stories that I know about Staffordshire and the surrounding area over the course of the coming week. However, 2020 hasn’t quite gone to plan and it’s entirely possible that I could fall victim to an attack of the mutant crayfish clones by Friday and so whether my bad intentions will materialise or fall by the wayside remains to be seen.

Anyway, I’m not sure if it’s a Staffordshire thing per se but something I’ve noticed about the churches in our area is their habit of juxtaposing the mundane with the magnificent. By way of example, I once found the tomb of Richard Samson, Bishop of Lichfield between 1470 and 1554 underneath a tea tray and a packet of hobnobs. I am also starting to think that the eleventh commandment is ‘Thou shalt have a stack of plastic chairs behind thy font’.

I suspect Pevsner would not approve but I think it gives churches a nice lived-in feel and exudes an eccentric sort of charm and therefore, I make no apologies for failing to remove the carton of milk and bottle of spray from my photograph of the remains of this stone cross in Tixall Church.

The cross stood on Kings Lowe, a Bronze Age Bowl Barrow on Tixall Heath before what remained of it was removed to the church for safe keeping. Its exact provenance is a mystery but in 1818 Sir Thomas Clifford of Tixall described it as having been placed there in around 1803, it being, ‘a very antique stone cross, which once stood before the gate of a ruined mansion in South Wales…It is of very hard moor-stone; the shaft, which has eight unequal sides, supports a tablet of an hexagonal form, adorned with very rude carvings; on one side, a crucifix, on the other, the virgin with the child in her lap. On the edge of the tablet is also a figure thought by some experienced antiqueries (sic) to be St. John the Evangelist’. The cross was said to mark the spot where Sir William Chetwynd of nearby Ingestre Hall was assassinated in 1494, although you might think that after 309 years the moment for a monument to a murder had passed. Who erected it and why they did so after all that time is not recorded.

In 1825, Alexander Wilson wrote a travelogue called ‘Alice Allan, The Country Town etc’ and appears to have had some sort of down the rabbit hole experience, proclaiming that, “When I entered Staffordshire, my straight-forward, regular travelling was at an end”. After insinuating that the residents of God’s own county used to get up to some Summerisle-esque unpleasantness involving wicker, Wilson relays the story told to him by an old countryman whilst driving across the heath. Sir William Chetwynd of Ingestre and Sir Humphrey Stanley of Pipe Ridware were both vying for the favour of King Henry VII, and so Sir Humphrey decided to rid-ware himself of his rival. A letter purporting to be from the Sheriff of Staffordshire was sent to Sir William requesting his attendance in Stafford at 5am the following morning. As he crossed Tixall Heath at dawn, accompanied by his son and two servants, he was ambushed by twenty men, several of whom were members of the Stanley family.

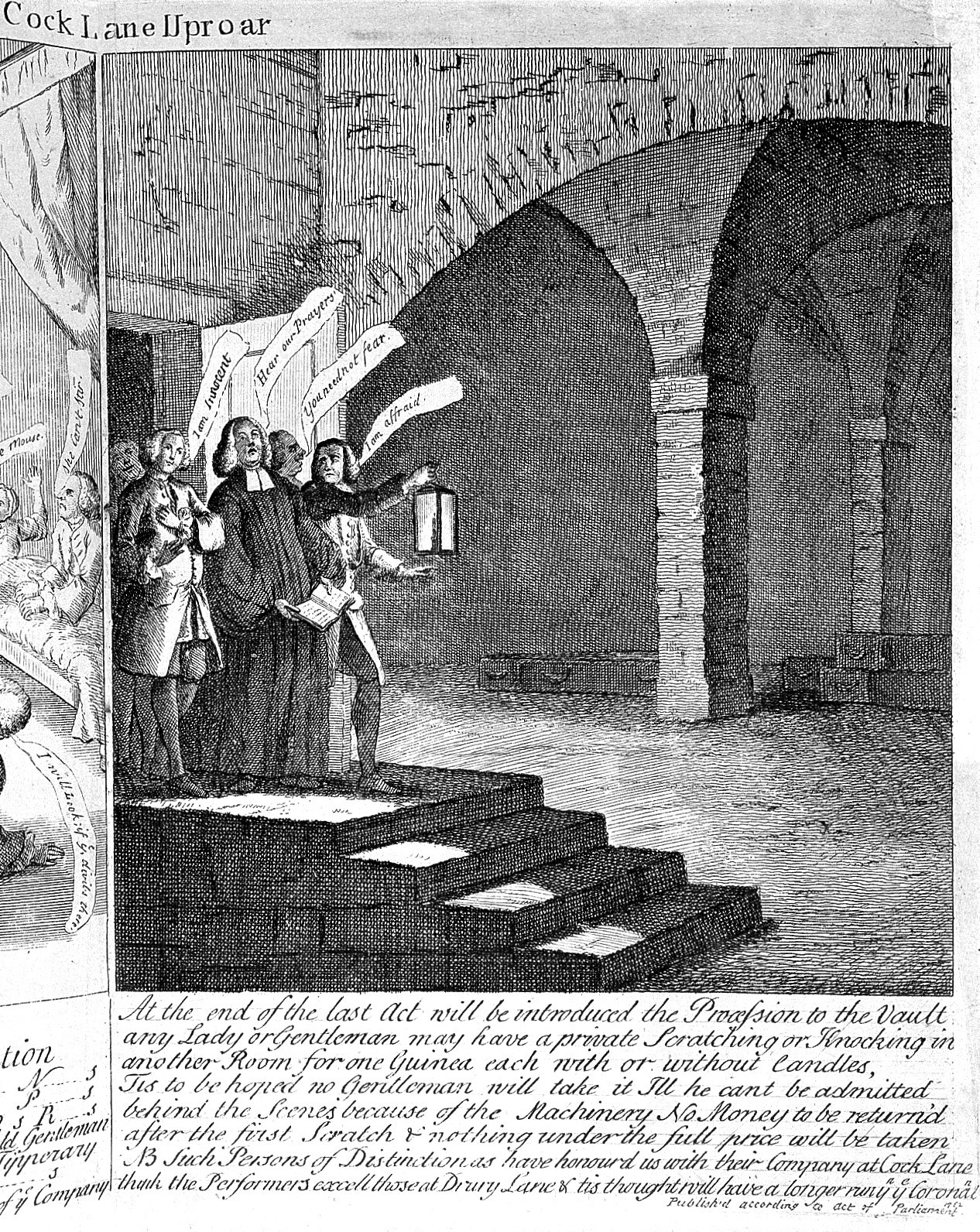

Despite a petition by the widowed Lady Chetwynd, Stanley literally got away with murder. Or did he? According to the story told to Alexander Wilson, some years after he’d killed Bill, Sir Humphrey was thrown from his horse at the same spot on Tixall Heath, breaking his neck. Official records show he died in 1505 and is buried amongst the great and also probably not very good at Westminster Abbey. As of yet, I can’t find a record of where or how he died and so perhaps that old countryman was right and karma did catch up with him in the end. Interestingly, it seems with the Stanleys, the rotten apple did not fall from the tree. An effigy in Lichfield Cathedral immortalises the disgrace of Sir Humphrey’s son, John, a man who committed a misdemeanor so grave that he was excommunicated and had to agree to spending the rest of his death being depicted as paying penance in order to be granted a Christian burial inside the Cathedral. There is no record of his specific wrongdoing but in 1867, the Very Rev Canon Rock suggested that Stanley’s offence may have been that he had spilled blood inside that sacred space. A 17th century drawing of the effigy by William Dugdale shows the stone Stanley bareheaded and bare chested, flanked by two bucks’ horns, wearing a skirt decorated with heraldic arms and armour on his legs. It’s a strong look to carry off for eternity although during the Civil War, the Roundheads did make some alterations in their own unique style… The much mutilated monument can still be found in the Cathedral so do go and see what’s left of him. I bet you there will be a stack of plastic chairs somewhere nearby too…

Lichfield Cathedral - Effigy of Captain Stanley: engravingShowing a print of the Stanley effigy. Anonymous.View Full Resource on Staffordshire Past Track

Lichfield Cathedral - Effigy of Captain Stanley: engravingShowing a print of the Stanley effigy. Anonymous.View Full Resource on Staffordshire Past Track

Sources:

Norton, E (2011) Bessie Blount: MIstress to Henry VIII, Amberley Publishing: Gloucester

https://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=77400

http://www.tixall-ingestre-andrews.me.uk/tixall/elytxhs.html

The Cathedral Church of Lichfield By AB Clifton

Handbook to the Cathedrals of England by Richard John King

Alice Allan, The Country Town etc by Alexander Wilson

Some remarks on the Stanley Effigy at Lichfield by The Very Reverend Canon Rock

Lichfield Cathedral - Effigy of Captain Stanley: engravingShowing a print of the Stanley effigy. Anonymous.

Lichfield Cathedral - Effigy of Captain Stanley: engravingShowing a print of the Stanley effigy. Anonymous.