The story of Beaudesert Hall features an incredible cast of characters. There’s Lady Florence Paget, the ‘Pocket Venus’ who eloped with her lover Henry Hastings, and married him on the very same day she was supposed to wed his best friend, Henry Chaplin. More famously, there’s Toppy aka The Dancing Marquess, and a film about the decadent 5th Marquess of Anglesey, ‘Madfabulous‘, has just been shown at Cannes. And of course, there is the first Marquess of Anglesey, who rests in peace in a crypt below Lichfield Cathedral (and no, I’m not going to make any missing leg jokes). For me though, it’s the beginning of Beaudesert and its (sort of) end that has captured my imagination most thanks to a fabulous guided walk and talk there last weekend with my friend JP.

Some of the most substantial remains still standing date back to the 15th century, when the place belonged to the Bishops of Lichfield. They christened it the ‘Beautiful Wilderness’, inspired by the surrounding countryside of Cannock Chase. The story of how it came into their possession is still unfolding and the idea that Beaudesert, first mentioned in the 13th century, may also be connected to two other nearby sites is an intriguing possibility. And how does the mysterious Nun’s Well fit into all of this?

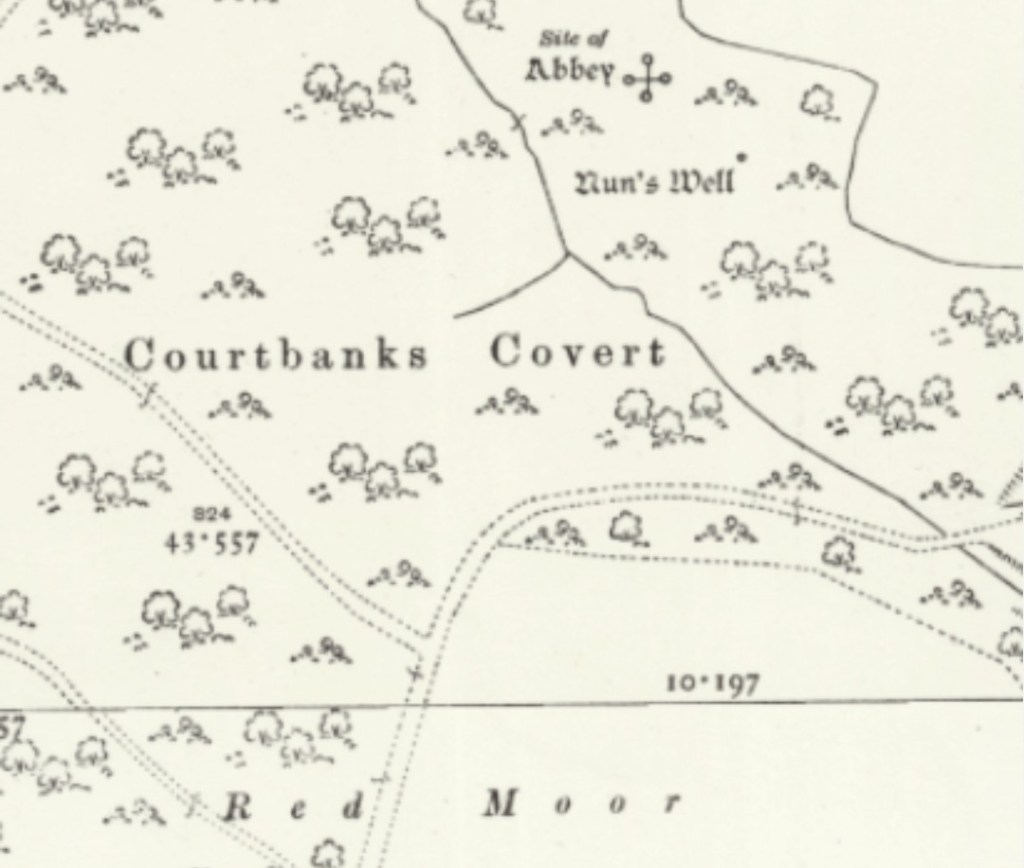

At Cannock Wood, a hermitage was established by King Stephen c.1130, which later became a short lived Cistercian Abbey dedicated to St Mary. Tired of being taken advantage of by the local foresters, the monks begged their benefactor, Henry II, to find their somewhere they could pray in peace. He agreed and swapped the site with what then became Stoneleigh Abbey. King Henry was happy with the exchange and turned Radmore, or Red Moor, into a royal hunting lodge. Despite the site of the Abbey being marked on maps, and evidence of a moated site, WH Duignan, the Walsall solicitor and antiquarian, cast doubt on the location suggesting heaps of furnace slag had been mistaken for ancient ruins. He believed the Abbey had instead stood within the ramparts of Castle Ring, where the foundations of a small building are still visible, although this has more recently been interpretated as another medieval hunting lodge.

Beaudesert belonged to the Bishop until the Reformation when Sir William Paget was given the house by Henry VIII. Paget had risen from humble beginnings to become a key member of the king’s court, thanks to his ability rather than ancestory. Many sources speculate he was the son of a nail maker in Wednesbury but what is certain is that this self-made man managed to keep his head, both physically and politically, throughout the turbulent times of the Tudor monarchs. The property stayed in the ownership of the Pagets until the 6th Marquess of Anglesey made the difficult decision to dispose of his Staffordshire seat in. In the end, he couldn’t even give it away and so the place was sold off piecemeal.

If you’ve read this blog before, you’ll know I have a fascination with what becomes of the fixtures and fittings of a lost country house and there are some tantalising trails to follow from Beaudesert. Pitman, writing for The Friends of Cannock Chase, described seeing, ‘Oak floors, decorative plaster ceilings, Jacobean overmantels, fire grates and irons of ancient dates, (and) marble bathroom equipment’, being dismantled by, ‘the bargain-maker’s men’. Many of these items were bought up by Sir Edward and Ursula Hayward and shipped down under to Carrick Hill House in Adelaide, including the Waterloo staircase, so named for the portrait of the 1st Marquess which hung above it. Oak from the Long Gallery went to Birmingham, where the City Council intended, ‘to keep it ready for use when occasion arises’. Did the Beaudesert panelling ever make it into a Brummie building? With the help of a local councillor, I’ve found a house in Armitage which was once a game larder on the estate and there are stories that more of the stonework found its way to Hanch Hall and to the collection of a man who kept curiosities in a disused rail station in Sutton Coldfield. (Yes, the temptation to go off track and delve further into this has been immense!).

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser, reporting on the sale in July 1935, buyers had 28 days to remove their new property. The demolition firm then had two years to, ‘clear the site, it being understood that he demolishes the building to the ground level and leave the site in a reasonably level and neat condition’. As we know, they never quite succeeded and thanks to the firm becoming bankrupt, some of Beaudesert Hall still survives, ready for another chapter in its long and eventful history. To uncover the full story so far, I can’t recommend enough that you book yourself onto a tour and let the experts guide you around this beautiful wilderness.

Sources:

The Friendship of Cannock Chase, Pitman

Staffordshire Advertiser, 27th July 1935

Staffordshire Advertiser, 16th November 1935

Birmingham Daily Post, 4th July 1977