I feared from the looks on my family’s faces that my interest in the macabre may have gone too far when I happened to mention during a meal at the Old Irish Harp that an inquest on the body of a genteelly dressed woman found ‘wilfully murdered’ in a wood near Sutton Coldfield had taken place not far from where we were sat, albeit 250 years prior. I thought perhaps it was time to find a different hobby. Embroidery perhaps? A pleasant pastime for sure, but turns out that for me it’s no substitute for finding and sharing a ripping yarn. And now that we’ve established that I am beyond all redemption, I want to regale you with a post about crime and punishment on the mean streets of Staffordshire.

On the evening of 26th October 1764, a little after 8 o’clock in the evening, Mr Thomas Hurdman of Alrewas was stopped by a footpad opposite St Michael’s churchyard. The Aris’s Birmingham Gazette cryptically reported the rogue was suspected to be a W_____ C_____ of Greenhill. I’m not sure why such nominal secrecy though, when they also published a description of him in the same report (not yet 20, about 5 feet 5 inches high, wide mouthed and wearing his own hair, if not altered, which was brown and short cut’). Despite being caught by one of the city’s constables, WC managed to quite literally give him the slip by sliding out of his coat, and legging it out of Lichfield in a linen frock. His freedom (and any semblance of anonymity) was short-lived however. In March the following year, newspaper reports reveal that the ID of WC was William Cobb and that he’d been sentenced by the High Steward of Lichfield, Fettiplace Nott, to be transported for his assault on Thomas Hurdman and making many violent threats of murder.

Ashmoor Brook, up Cross in Hand Lane, was the scene of another robbery which went awry. In Lichfield March 1833, a notorious local character known as Crib Meacham, a name apparently derived from his success in various pugilistic encounters, was charged with robbing a Mr Lees of Stoneywell. According to Lees, Meacham was one of a gang of four who attacked him and his wife. The pair were in possession of a large sum of money but it was Mrs Lees who was holding the purse strings at the time and the thieves had allowed her to run away. She soon returned with assistance and it was the robbers turn to run, leaving a gagged Mr Lees unharmed but relieved of his relatively empty purse and hat. Meacham was arrested later that evening but as of yet, I cannot tell you anymore about him, neither the fights which earned him his nickname in the past nor the fate he earned from his part in the robbery.

I can tell, however, tell you much more about Robert Lander aka Bradbury a cordwainer of Milford near Stafford who robbed Solomon Barnett, a wax chandler of Liverpool in March 1798. The newspaper reports at the time give not only a physical description (Lander was a stout built man, 5ft 5 inches, 25 years of age wearing a blue coat, a striped fancy coloured waistcoat, and thickest breeches, torn upon the left thigh and patched upon both the knees). It also gives his villain origin story, starting at his childhood home of Haywood near Stafford. When his Dad died, he inherited a few hundred pounds. At the age of 21 he got turned down for a job at the Board of Excise and so went to work for a gentleman in the wine and spirit trade instead. This, it seems, may have been the start of his downfall. During his employment he is said to have remained in a permanent state of intoxication, eventually absconding and taking with him a watch belonging to his master. He sold it at Stafford where he enlisted into a Regiment of Foot but ended up, somewhat ironically, in the shoe making business. This didn’t last long either and neither did his subsequent enlistment into four other regiments. His career in crime also came to an abrupt end when he was found guilty of the robbery of Solomon Barnett and sentenced to death at the Stafford Assize. When the judge prayed that the Lord would have mercy on his soul, it was reported Lander replied, ‘G__d d___n you and the gallows too. I care for neither’. I assume he said it in full but that his blasphemy was censored by the Chester Chronicle. He was executed in August 1798 and the parish register of St Mary’s Stafford records that, along with Edward Kidson, Robert Lander alias Bradbury was executed _ _ _ _ _ _ _.

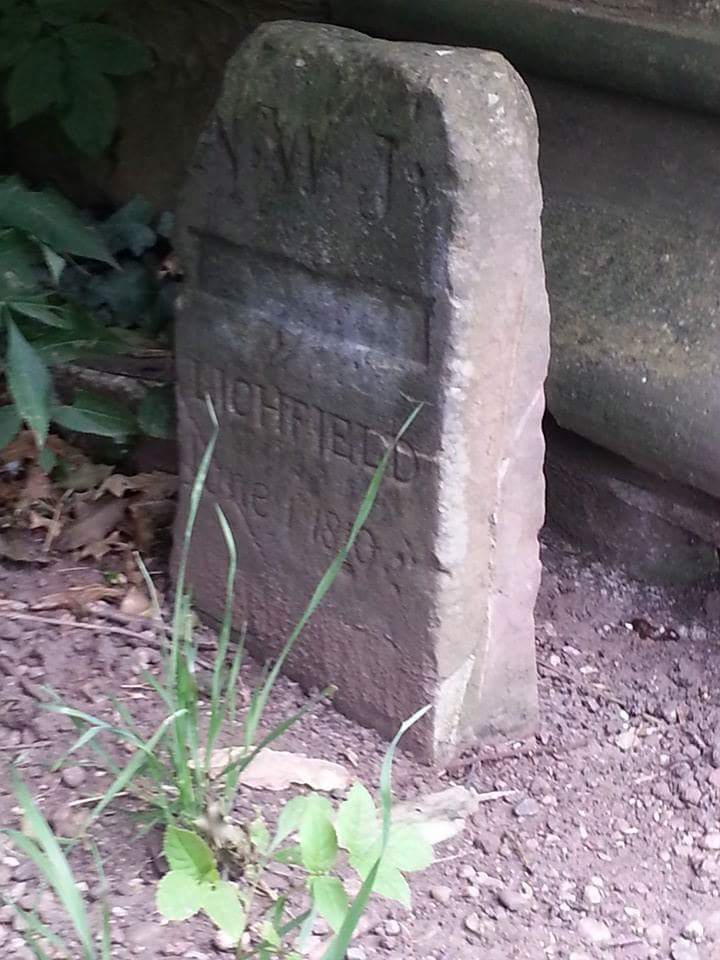

These are all true crime stories, but it would’t be Lichfield Lore without a bit of folklore would it folks? You’ll be relieved to know I’m not going to go down the Turpin turnpike road but I am going to give a dishonorable mention to Tom ‘Artful’ Arnott, a highwayman who was supposedly executed, gibbeted and, eventually, buried at this crossroads in Cannock.

Although Arnott’s grave is marked on old maps there are no records of anyone of that name ever being executed. Intriguingly though, there is a record of a Thomas Arnott being buried on 1st September 1777 at St Luke’s in Cannock. Clearly a man can’t be buried in two places at once but it’s the right kind of era and area. Then there’s a Thomas Arnott mentioned in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette in October 1792 for absconding from his master’s service in Birmingham. Intriguingly, after given a description of him (35 years old, five feet five inches, marked with the Small Pox, dark lank hair, and lightly made, wearing a blue coat), it mentions that prior to his work as a stamp, press, lathe and die maker, he had been employed as a forger. Do they mean the criminal variety and if so, does this strengthen the case for him being our Tom? Just to add an extra layer of intrigue, there was yet another absconding Thomas Arnott, who was apprenticed to a Whitesmith in Worcester but ran away on 5th April 1803. He’s described as 5 feet two inches, black curled hair, wearing a blue coat with yellow buttons, a green striped cashmere waistcoat with yellow buttons and dark velveteen breeches. In that outfit, if he did become a highwayman, he’d have been a very dandy one indeed. Could any of these be the legendary Arnott? Did he even exist in the first place? All I do know is that this story is one T__B__C__________.

Sources

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 5th November 1764

Aris’s Birmimgham Gazette 18th March 1765

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 25th March 1833

Staffordshire Advertiser 24th March 1798

The Chronicle 7th September 1798

Chester Chronicle 17th August 1798

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 8th October 1792

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 2nd May 1803