Lichfield is about as far as you can get from the sea. Somebody once wrote to the Guardian to say there was a plaque somewhere in the city making this claim but I’ve never seen it. However, being stuck in the middle of the country has not prevented the formation of the Lichfield Lighthouse Company, a group who meet at the Kings Head to sing sea shanties each month. It also didn’t stop me from heading out to look for shells in the city centre yesterday.

I’d read about the London Pavement Geology project over breakfast and I persuaded the other half to put his geology degree to good use and help me find out what Lichfield is made of, other than the ubiquitous sandstone (lovely though it is).

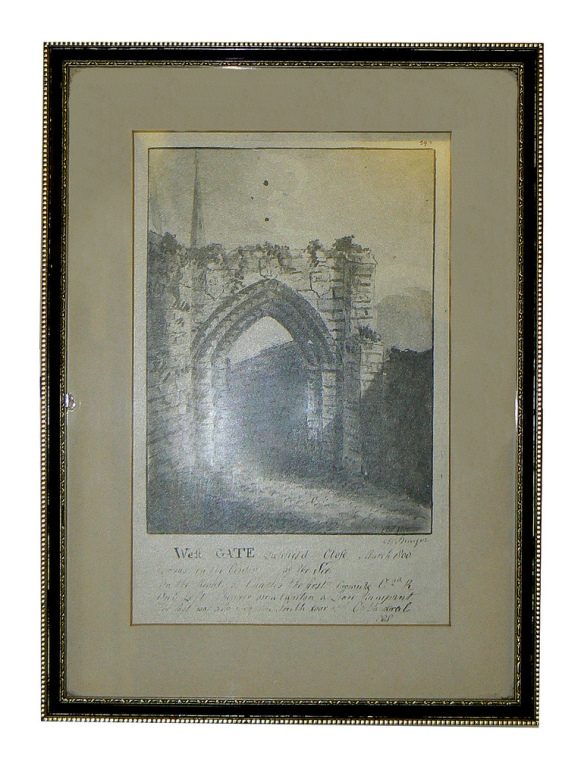

Our first port of call was another of landlocked Lichfield’s nautical links. Unless you live under a rock, you’ll probably be familiar with Beacon Park’s statue of Captain Smith which someone from Hanley in Stoke on Trent tries to appropriate whenever there’s a new chapter in the Titanic story, due to the mistaken belief that the statue was originally intended for their town. On this occasion, it wasn’t the bronze captain but the plinth he was stood on that interested me. The nearby plaque told me it was Cornish Granite, a material which has also been used at the Titanic Memorial in London and the memorial at Belfast. I wonder whether there are any symbolic reasons for choosing this stone alongside the practical and aesthetic ones?

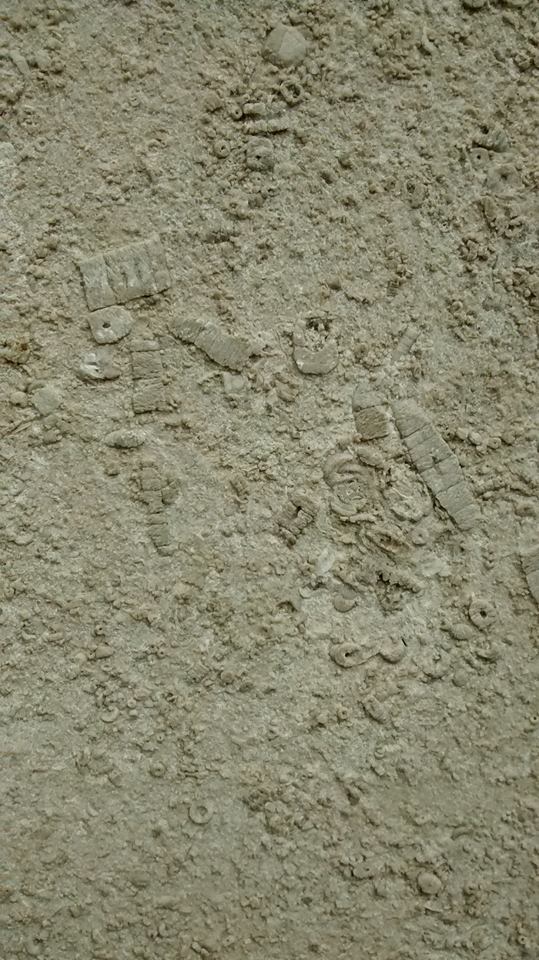

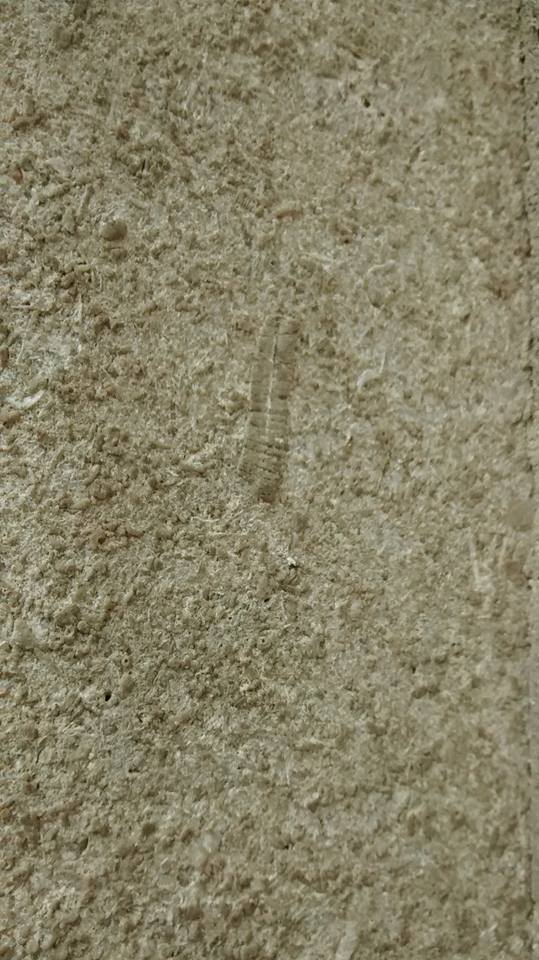

Not far from the Captain, King Edward VII stands on a base made of Hopton Wood stone. Get up close and you can see that the limestone is full of fossils including (and please correct me if I’m wrong) corals, crinoids and brachiopods from around 350 million years ago when the area that was to eventually become Derbyshire was under water. Lichfield wasn’t always so far from the sea! It seems a similar stone has been used for the plinth Samuel Johnson sits on in the Market Square, as that too is full of fossils.

Of all the building materials we saw on our travels, the most unusual were to be found in a wall on Christchurch Lane. According to a booklet on the history of Leomansley compiled by the Friends of Christ Church, it was built by Cloggie Smith who used anything suitable that he had in his yard at the time. So, no Portland Stone here, just two Belfast Sinks. Are there any other examples of unorthodox construction materials used in and around the city?

Of all the building materials we saw on our travels, the most unusual were to be found in a wall on Christchurch Lane. According to a booklet on the history of Leomansley compiled by the Friends of Christ Church, it was built by Cloggie Smith who used anything suitable that he had in his yard at the time. So, no Portland Stone here, just two Belfast Sinks. Are there any other examples of unorthodox construction materials used in and around the city?

You’ve probably guessed that I am way out of my depth when talking about geology, but the point is that after eleven years, seven months and two days here in Lichfield, someone made me look afresh at things so familiar that I barely saw them any more. Sometimes, the most amazing things are right under your nose. Or, in this case, under Dr Johnson’s and King Edward VII’s noses.